- Minorities & Smoking – Home

- Taking Notice

- The Power of Tobacco Marketing ▼

- A History of Marketing Menthol to Minorities

- Supporting and Suppressing Minority Communities ▼

- Targeting Latinos

- Targeting Minority Women: A Marginalized Market

- Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act

- The DOC Response

- Recent Struggles

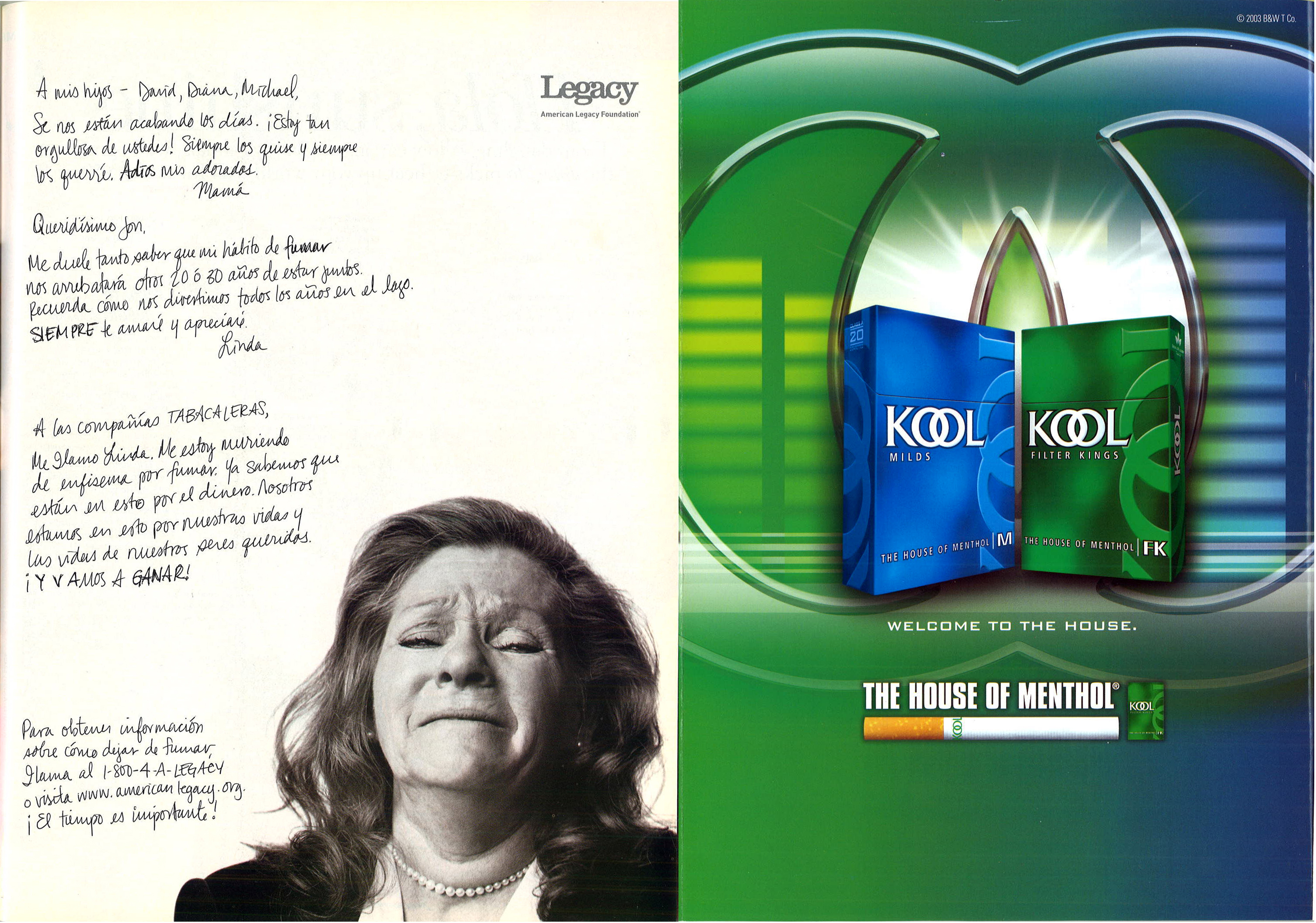

“A mis hijos”/ “The Women of Menthol”

(To my children)

American Legacy Foundation advertisement in Spanish and Kool advertisement in same issue of magazine

Latina, page 49 and advertising insert

June 2003

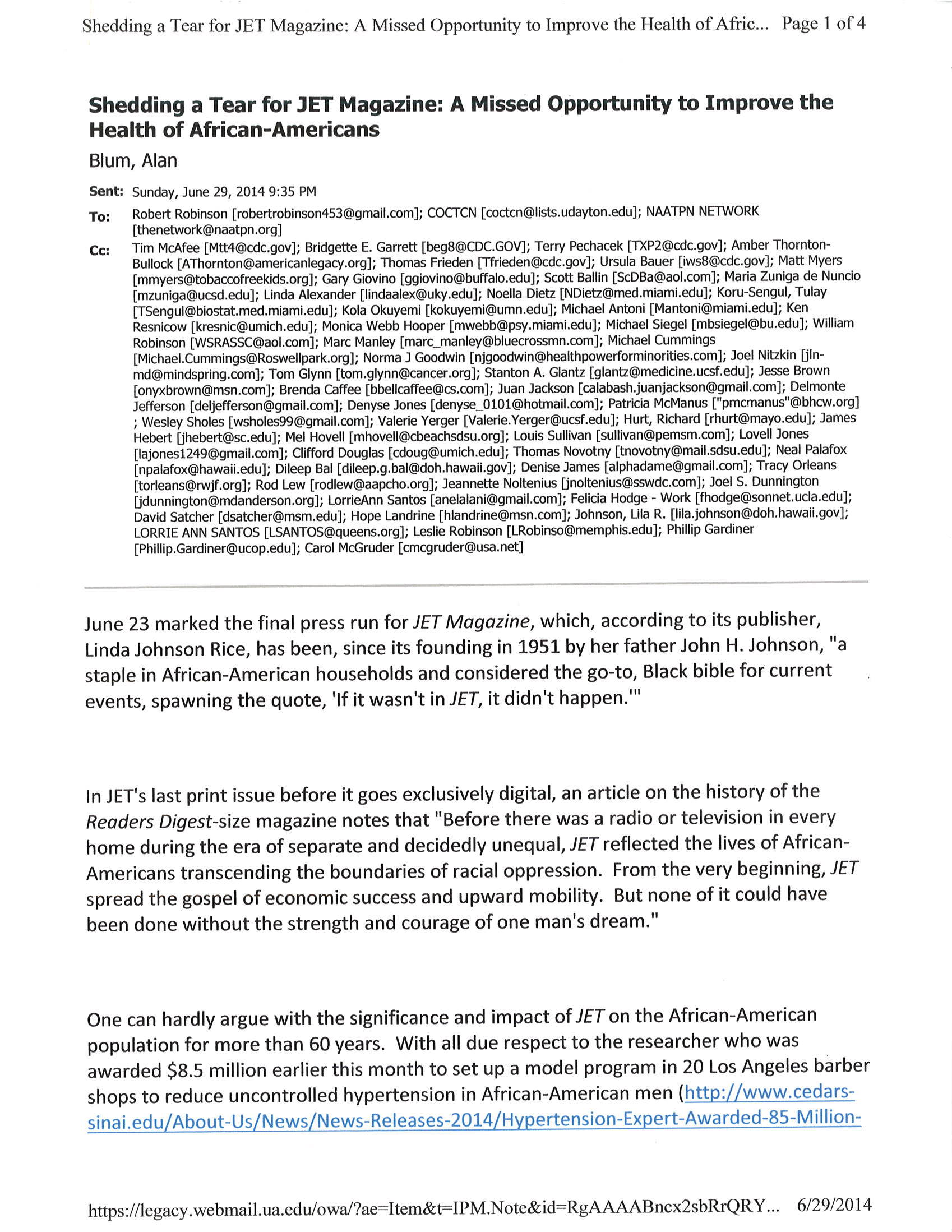

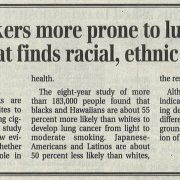

“Shedding a Tear for JET Magazine: A Missed Opportunity to Improve the Health of African-Americans” (4 pages)

Email from Alan Blum, MD, to various anti-smoking activists about the tobacco industry’s influence on the black press

June 29, 2014

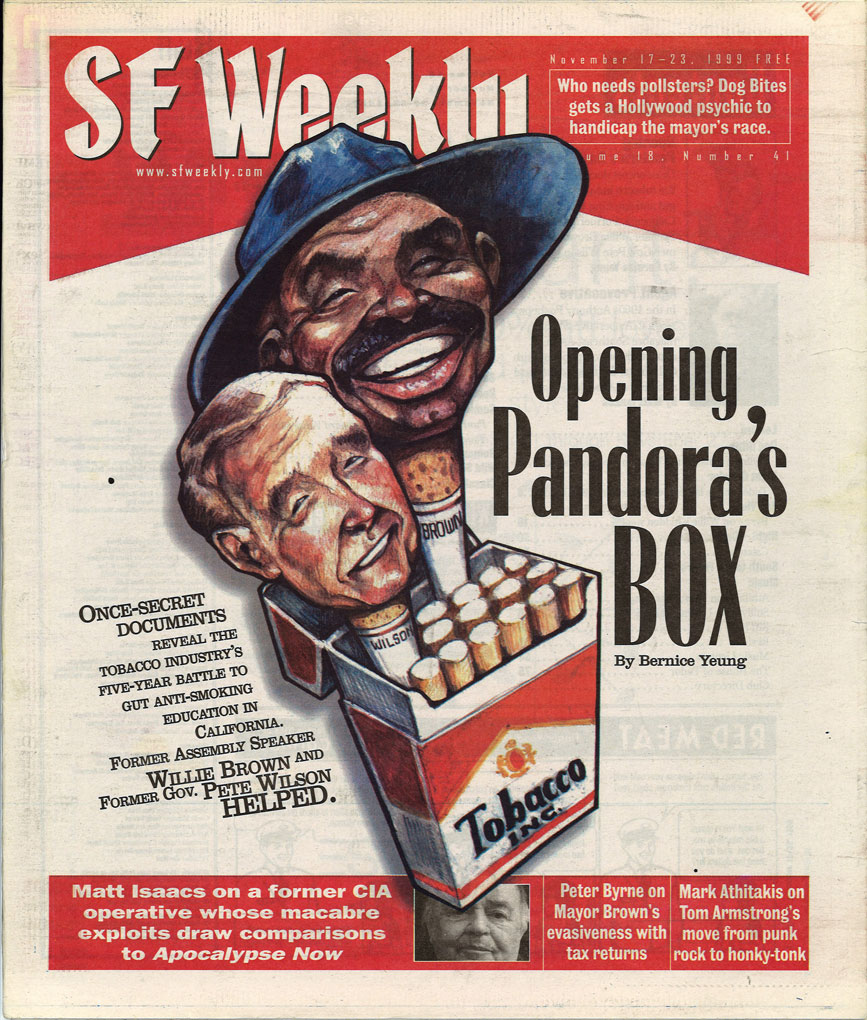

“Opening Pandora’s Box” (9 pages)

News article by Bernice Yeung about the tobacco industry’s efforts to prevent anti-smoking education in California, aided by former Assembly Speaker Willie Brown and former Governor Pete Wilson

SF Weekly, pages 12-13, 15-17, 19, 21-22

November 17-23, 1999

“Smoking Cessation Within the U.S. Hispanic Community” (4 pages)

Medical article by Lisa Cabral, MD

Caring For Hispanic Patients 2005, pages 9-12

2005

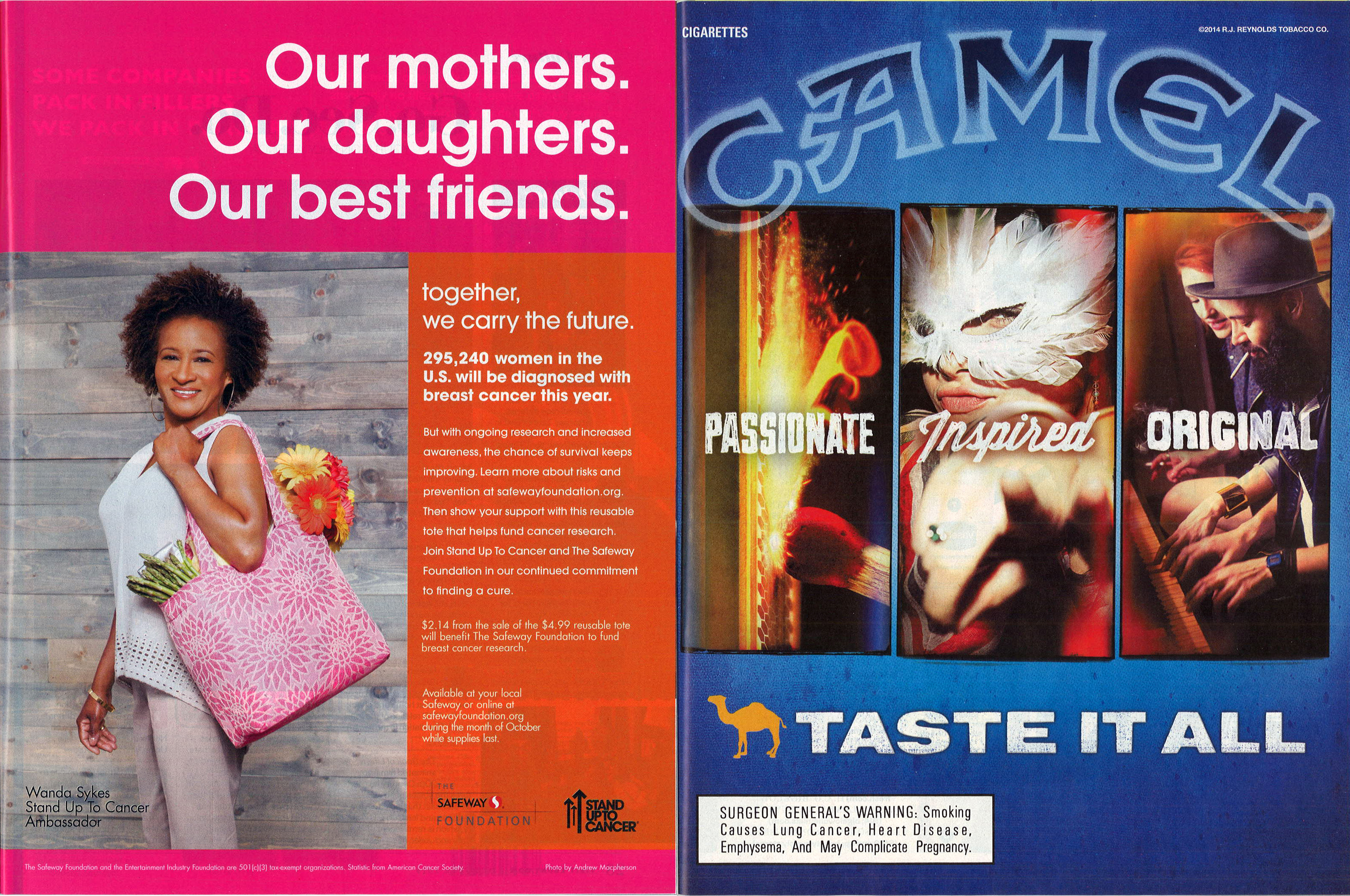

“Our mothers. Our daughters. Our best friends”/ “Passionate – Inspired – Original”

Stand Up To Cancer advertisement and Camel advertisement in same issue of magazine

Ebony, pages 27 and 51

October 2014

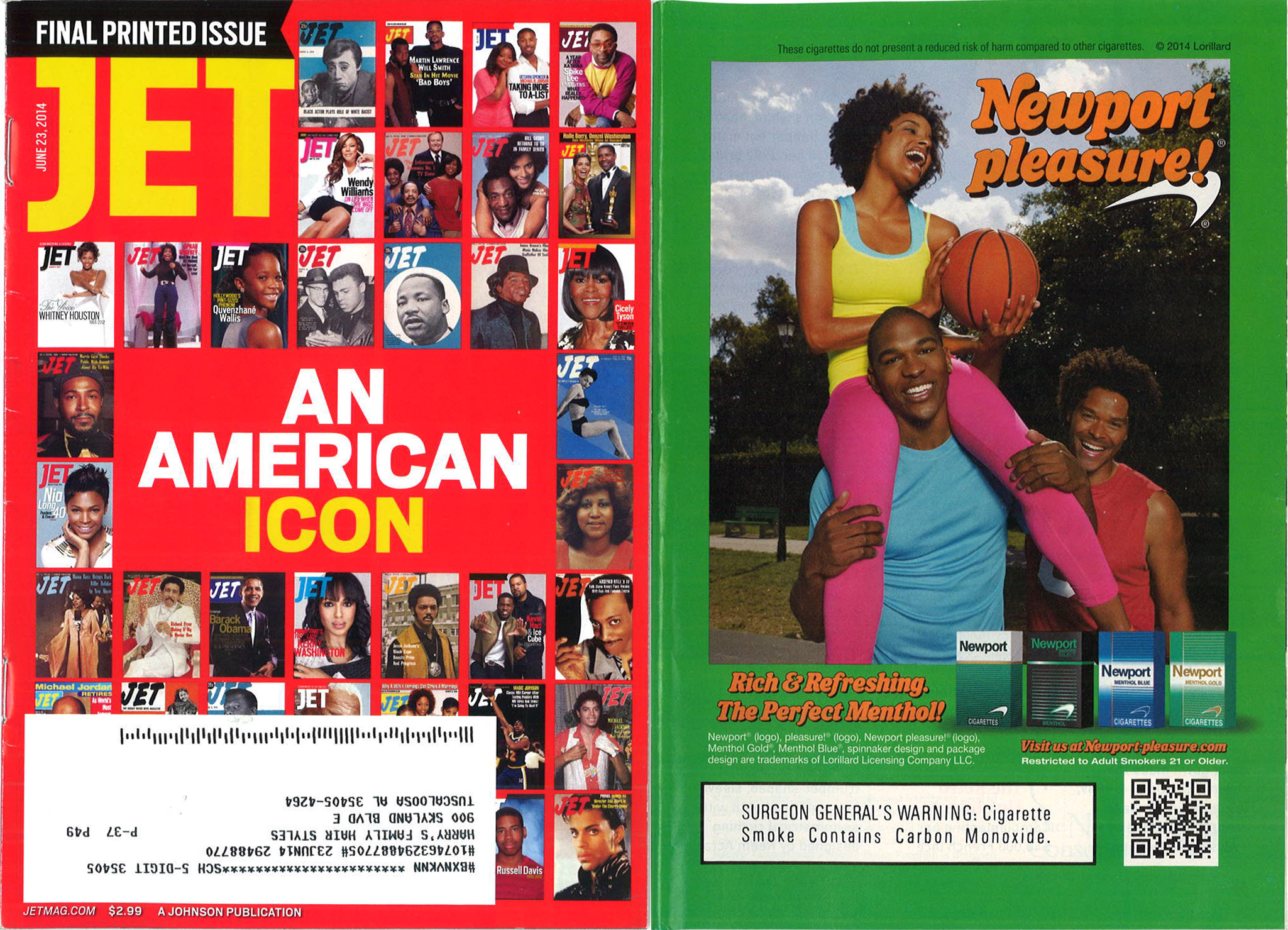

“An American Icon”/ Newport advertisement

Final print issue of Jet, front cover and page 57

June 23, 2014

Newport advertisement/ “Fighting Breast Cancer”

Advertisement and magazine article by Michelle Meyer in same issue of magazine

Essence, pages 86 and 125

October 2009

Recent Struggles

Foremost among organizations seeking to end tobacco consumption by African Americans is the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network (NAATPN). NAATPN offers smoking prevention and cessation programs and resources for individuals, organizations, and communities alike.

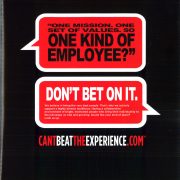

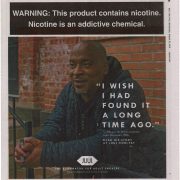

Truth Initiative (formerly known as the American Legacy Foundation) has a national advertising campaign called “Truth,” which aims to end teen smoking in the U.S. through the production of television and digital content that encourages teens to shun tobacco. As part of this effort, the organization ran an ad campaign called “Finish It” in 2017 that highlighted “the ways in which cigarette marketers disproportionately target disadvantaged groups.” One such way is via a far greater number of tobacco retailers and advertisements in areas with large minority populations than in other areas. The campaign brought attention to the “discriminatory nature of tobacco advertising.”

The National Association of African Americans for Positive Imagery (NAAAPI) (1990-2005) has striven to end the marketing of alcohol, tobacco, and other harmful products to African-American communities by mobilizing African Americans to live healthy lifestyles, promote positive individual and community imagery, and foster environments free of health disparities. In the 1990s, the group’s efforts were instrumental in preventing the introduction of the cigarette brands Uptown and X to the American market—brands specifically targeted at African Americans. In recent years, NAAAPI has also campaigned to encourage parents and other adults to prevent children from being exposed to secondhand smoke.

The Health Education Council, established in 1979, collaborated with low-income communities across Northern California to support health and well-being. In May 2018, the Council launched a project called Lucha Tobaco, in which it partnered with Latinos in 14 Northern California counties to prevent and control tobacco use in their communities. One of the Council’s notable past programs was the Break Free Alliance (2000-2014), which aimed to reduce tobacco use in populations of low socioeconomic status.

The California-based African-American Tobacco Control Leadership Council (AATCLC), formed in 2008, has assisted organizations in Chicago, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Baltimore, and California cities in adopting and implementing legislation establishing buffer zones around schools in which the sale of all flavored tobacco products, including menthol, is prohibited.

Since 2000 much of the literature cataloguing the advertising and promotion of tobacco products to minority groups has been a rehashing of a handful of essays written in the mid-1980s. Most articles decry a litany of injustices wrought on these groups by the tobacco industry. The prevailing tone of the authors is one of moral outrage. Yet although the tobacco industry disproportionately targeted minority groups, there was a decades-long indifference in minority communities – and in some quarters, outright hostility – toward addressing the problem.

Proposed solutions have been few and far between, owing in part to the reluctance on the part of minority opinion leaders to criticize one another and risk creating the appearance of a divided community. The problem is especially worrisome at the governmental level, where grants are awarded to earnest but inexperienced individuals for ambitious-sounding pilot projects on smoking cessation or prevention, with little likelihood that they can or will be replicated. Research on the study of tobacco promotion to minority groups is mired in a descriptive phase, which invariably includes counting the number of cigarette signs on convenience storefronts in minority neighborhoods (as opposed to challenging the existence of racial segregation and inappropriate zoning laws) and reciting the litany of tobacco industry gifts to legislators.

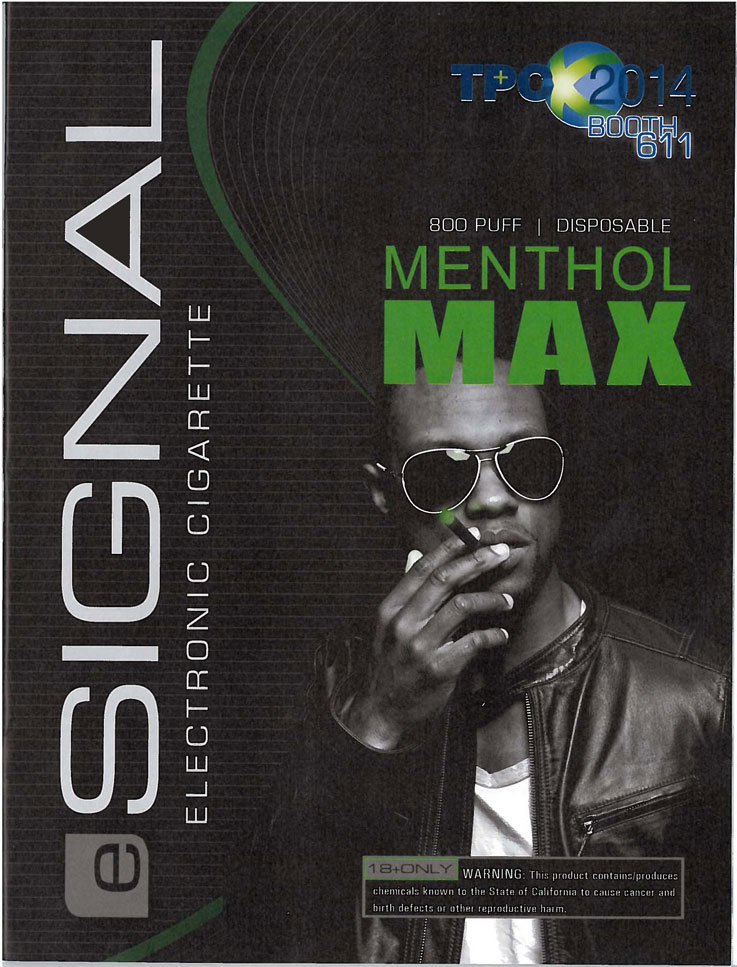

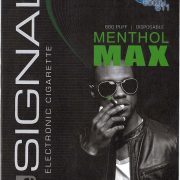

Although increased calls for federal, state, and local legislation – on taxes, warning labels, teenage access to tobacco, and advertising restrictions – have stimulated greater public dialogue, they are less effective steps toward reducing demand for tobacco products than are major paid campaigns in the mass media to undermine the tobacco industry and its brand name products. But tackling the smoking pandemic must also take into account the dynamism of the tobacco industry and its allies, who continue to create ways to insinuate tobacco products and electronic cigarettes into the social fabric of African-American communities.

More On: Recent Struggles

Contact

Alan Blum, M.D., Director

205-348-2886

ablum@ua.edu

© Copyright - The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society