Diabetic Bread, Goat Milk Formula, Soda, Sun Lamps, and Cigarettes

A potpourri of advertisements in the Journal of the American Medical Association, 1880’s – 1950’s

Introduction

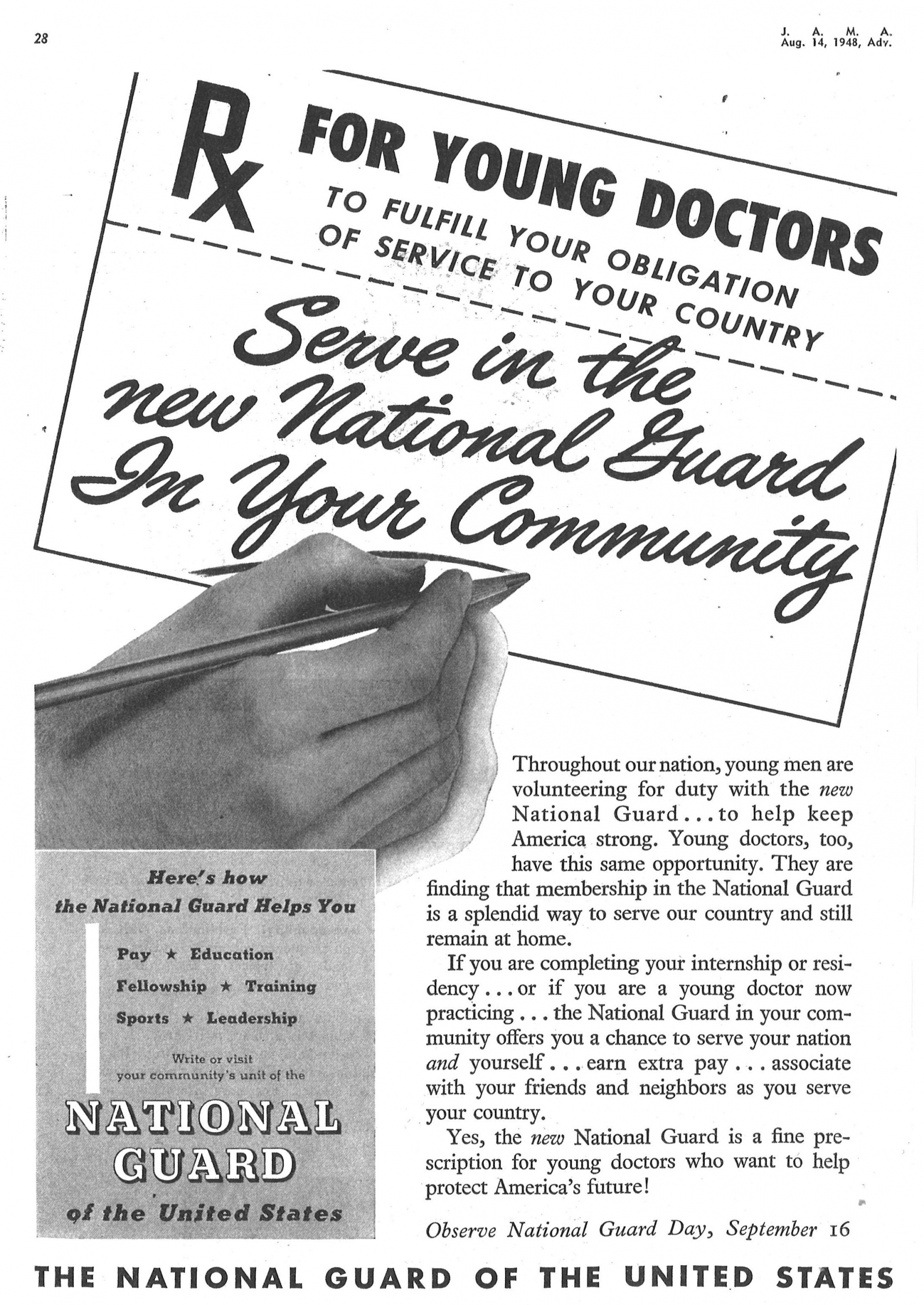

This exhibition features nearly 300 advertisements in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) from its first issue in 1883 to the 1950s, as well as ads in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) and other journals aimed at influencing physicians’ prescribing practices and personal consumption preferences. In addition to ads for drugs and medical devices, JAMA — the most widely circulated medical journal of the era — accepted advertisements for a broad range of consumer products, including automobiles, infant formulas, sanitariums, shoes, cosmetics, vitamins, cereals, hotels, airlines, soda, fruit, eggs, meat, milk, and…alcohol and cigarettes.*

Peer-reviewed medical journals like JAMA publish research articles and commentaries after scrutiny by outside experts. The journals whose content is the most cited by researchers and practicing physicians alike are those with the strongest peer-review process. JAMA publishes just 12% of the more than 10,000 manuscripts it receives each year.

But the paid advertisements for medications and medical devices in JAMA and other journals do not undergo the same degree of peer review as manuscripts. Although drug companies must adhere to marketing guidelines set by the Food and Drug Administration, they have carte blanche with the frequency of ads and the images and slogans used in the ads. Throughout the past century, this has led to the emergence of adverse reactions not previously identified in the testing of the drugs. For example, overenthusiasm in prescribing newly introduced antibiotics in the 1950s to 1970s led to the dramatic increase of resistant strains of bacteria in ensuing decades. Diethylstilbestrol (DES), a synthetic estrogen advertised from 1941 to 1971 as a treatment during pregnancy to prevent miscarriages, was found to cause genital cancers in offspring. Beginning in the late-1990s, ubiquitous advertisements touting the safety and efficacy of the semi-synthetic opioid pain medication OxyContin were published in numerous medical journals, laying the foundation for a crisis of addiction and deaths.

Disputes between the medical profession and pharmaceutical companies over exaggerated claims in the advertising of drugs date from the late-nineteenth century. George Simmons, MD (1852-1937), general secretary of the American Medical Association (AMA) and the editor of JAMA from 1899 to 1924, was an outspoken opponent of pharmaceutical industry hucksterism and the commercialization of the practice of medicine. As Yale University historian Peter Swenson recounts in his seminal book Disorder: A History of Reform, Reaction, and Money in American Medicine, until the 1920s the drug industry was one of the AMA’s bitterest enemies, with reformer Simmons warning that working with pharmaceutical advertisers was “about the same as Faust trying to make a deal with Mephistopheles.”

After 1924, however, under Simmons’ successor Morris Fishbein, MD (1889-1976), drug advertising accounted for an ever-increasing share of the AMA’s operating expenses. While Fishbein crusaded against health quackery and misleading drug advertising in the lay press, he was cultivating close ties with drug company executives and commercializing JAMA. The AMA created a Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry and a Committee on Foods that gave a Seal of Acceptance to advertisers in the journal. For many years, infant formula was one of the most advertised products in JAMA because the Committee on Foods required the formula industry to advertise only to the medical profession. Thus the AMA earned lucrative revenue in exchange for giving its endorsement to proprietary interests.

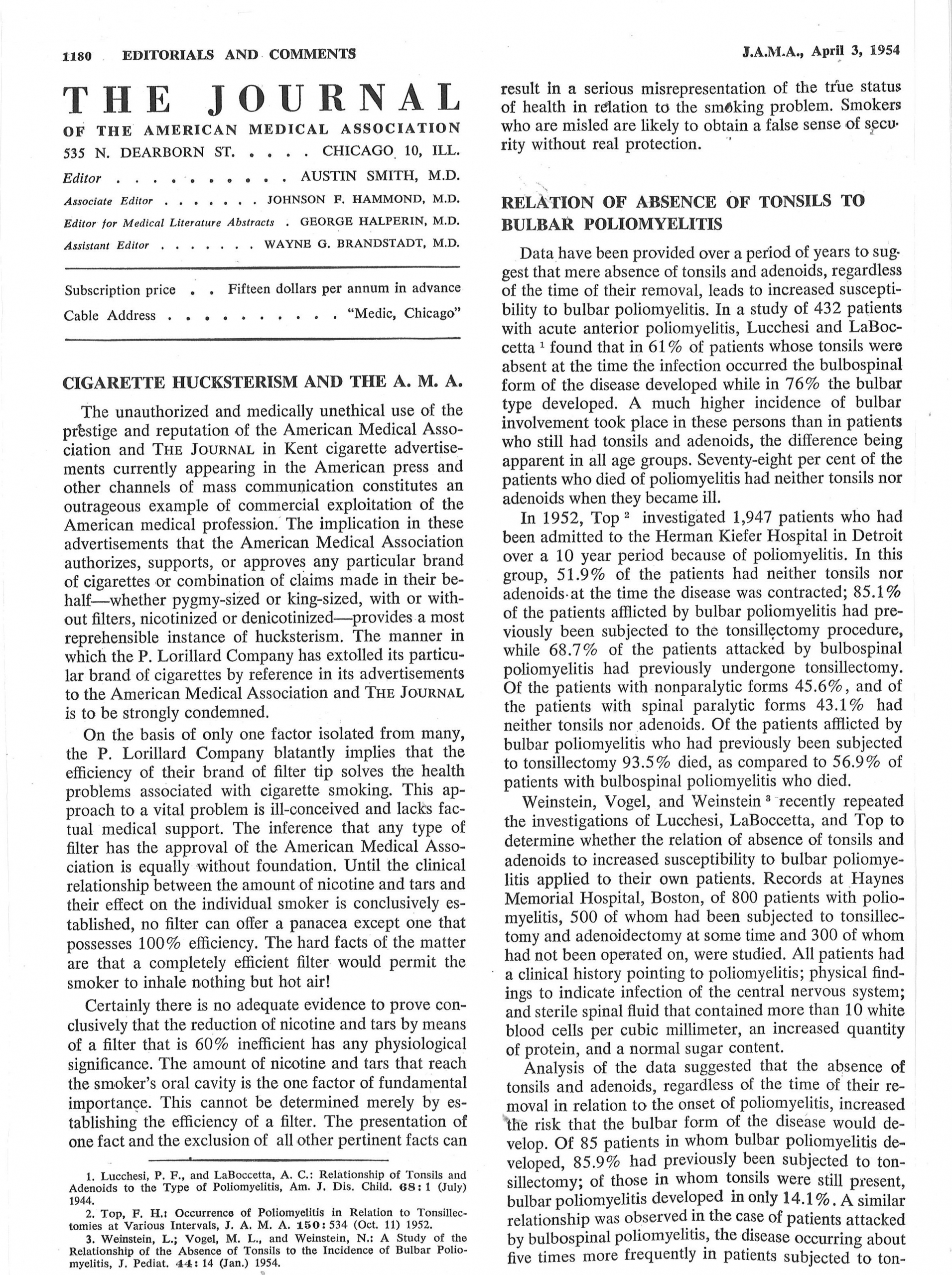

Editor Fishbein also opened the door to cigarette advertisers. By the 1930s, as smoking was dramatically increasing among men and women, cigarette advertisements were appearing regularly in JAMA and The New England Journal of Medicine in the U.S. and in The Lancet and the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in the United Kingdom, in spite of –- or perhaps because of -– the growing evidence that smoking caused lung cancer. For over 25 years until 1954, JAMA accepted cigarette advertisements that claimed reduced risks to health and encouraged physicians to smoke certain brands and recommend them to their patients.

In 1957, in a presentation to medical editors and journalists at the Third Congress of the Union Internationale de la Presse Médicale, Joseph Garland, MD (1893-1973), editor of NEJM from 1947 to 1967, discussed the responsibility of editors for the “character and quality of the medical advertisements that our journals accept and that are so vital to their prosperity.” He was concerned that commercial pressures engendered by the rapid growth and prosperity of the pharmaceutical industry were leading to “an increasingly uncomfortable awareness of our own editorial obligations in the matter.” Yet under Garland’s tenure, NEJM, like JAMA, accepted scores of cigarette ads well after the publication in the late-1940s in The Lancet and the BMJ of the landmark epidemiological studies by Hill and Doll on smoking and lung cancer. JAMA, too, published major review articles on smoking and lung cancer as early as 1941.

Ironies abound in this exhibition. It was not unusual during Fishbein’s 25-year tenure as editor until his forced resignation in 1949 (following which he became a paid consultant to P. Lorillard Tobacco Company, makers of Kent cigarettes) for the reader to come across advertisements for cigarettes in the same issue as ads for radium in cancer treatment and X-ray machines in the screening for lung cancer. Ads for candy, chewing gum, ice cream, and soda appeared in the same issue as ads for toothbrushes and weight-loss medications. Even after publishing countless advertisements over four decades for sanitariums and makers of medications for the treatment of alcoholism, JAMA accepted a series of advertisements for Schenley whiskey in 1953.

Alan Blum, MD

Director, The University of Alabama Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society

June 23, 2025

Click the links below to be taken to the corresponding section.

The Early Years | Medical Schools | Infectious Diseases I | Books | Classifieds | Sanitariums | Automobiles | Cigarettes