Introduction

Quick, what color is menthol?

No, it’s not green. Menthol is a colorless anesthetic, like Lidocaine that the dentist uses to mask pain. Accidentally discovered by a young man, Lloyd “Spud” Hughes, in the 1920s to reduce the harshness of smoking after he’d stored his cigarettes in an old tin of menthol crystals that his mother insisted he inhale for his asthma, he patented the idea.

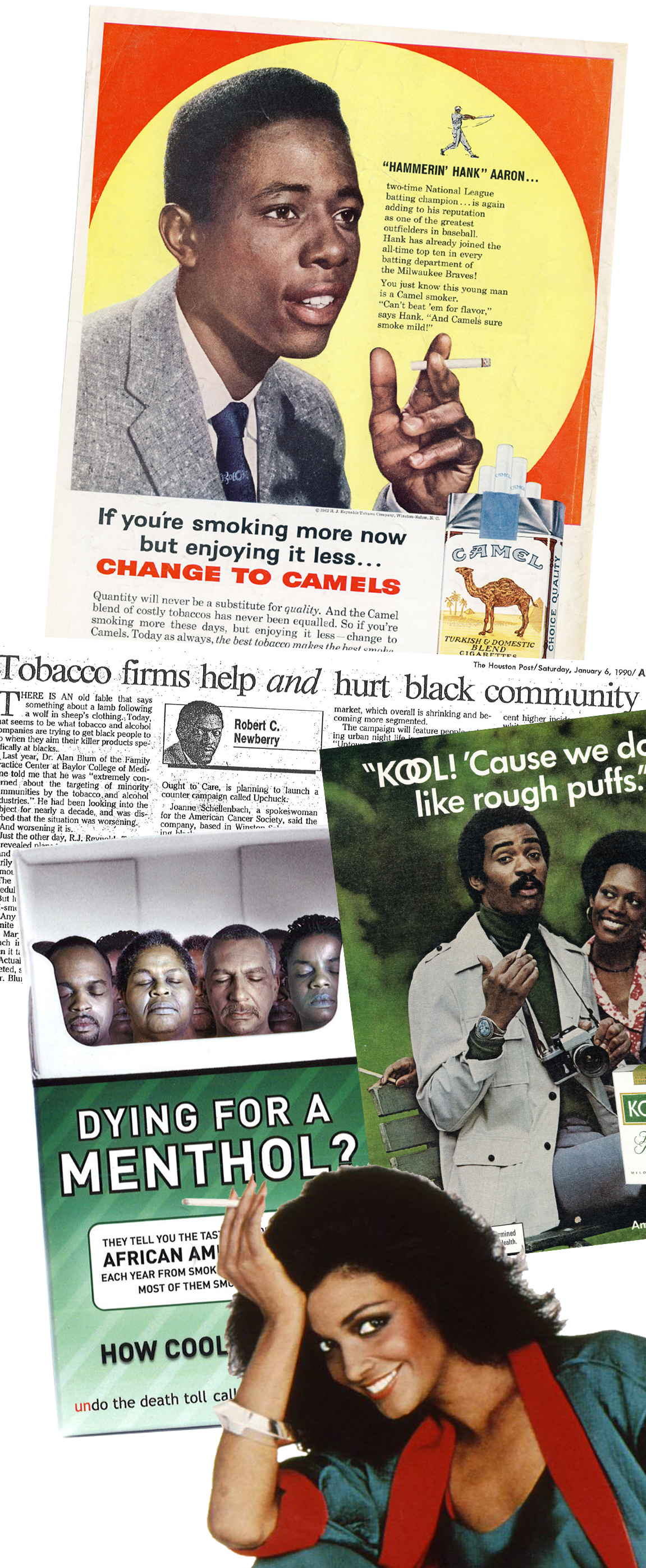

By the 1960s, mentholated cigarettes were especially popular among African Americans, to whom they were heavily marketed. Three brands—Brown & Williamson’s KOOL, Lorillard’s Newport, and R.J. Reynolds’ Salem—made up the lion’s share of menthol cigarettes. Not a single advertisement for a non-menthol brand ever appeared in the leading African-American magazine Ebony in its 70-year existence under its original publisher—and not a single article ever appeared on the leading preventable cause of death among African Americans: cigarette smoking.

But menthol was far from the only targeting of African Americans by the tobacco industry. Cultural events such as the Ebony Fashion Fair, an annual national tour hosted by black sororities in dozens of cities, was sponsored by R.J. Reynolds’ More cigarettes throughout the 1980s. Brown & Williamson’s KOOL Achiever Awards gave cash grants to black community leaders throughout the nation. Philip Morris, maker of Benson & Hedges, Virginia Slims, Marlboro and other menthol brands, was a prominent sponsor of meetings of black newspaper publishers and black journalists, as well as of the prestigious Spingarn Medal annual dinner of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Music festivals, concerts, and night club performances—jazz, blues, gospel, hip-hop, and rap—have been the major form of tobacco promotion to African Americans from the 1960s to the present.

By 1985 the Task Force on Black and Minority Health of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services would report that there were 58,000 excess deaths annually among African Americans compared with the death rate for the white population. Principal among the rising causes of death were cardiovascular disease and lung cancer—the two major consequences of cigarette smoking, which is the only risk factor that is both entirely avoidable and actively promoted. At that very moment, Philip Morris could advertise in New York City’s black newspapers that Mayor Ed Koch’s proposed restrictions on smoking in the workplace would promote “a perfect backdrop for employers who wish to discriminate against minority employees,” presumably because a higher proportion of blacks smoked than whites.

The extensive public relations campaign by the cigarette companies may explain the virtual absence of black leaders who denounced the targeting of African Americans by the tobacco industry. Grassroots anti-smoking activism gradually emerged only in the late-1980s. For their part, Philip Morris executives would accuse critics of paternalism, suggesting that it was patronizing to think that African-American consumers were incapable of making a free choice of whether or not to smoke. Defending his company’s support of leading black civic organizations, dance companies, and arts groups, CEO George Weissman cited numerous other national and local sponsorships, including the Boy Scouts, the YMCA, museums, and hospitals. In other words, “We advertise to everybody.”

More than half a century after cigarette smoking was identified by the Surgeon General as the nation’s leading preventable cause of death and disease, far more funding is still spent on repetitive or redundant research than on action against smoking such as paid counter-advertising in the mass media. Although progress has been made in reducing cigarette smoking among African Americans and in restricting cigarette advertising, the problem remains a significant one, requiring greater commitment—and action—on the part of health professionals, government agencies, academia, and the business community alike to end the smoking pandemic.

Alan Blum, MD

Gerald Leon Wallace, MD, Endowed Chair in Family Medicine

Director, Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society

The University of Alabama School of Medicine, Tuscaloosa

ablum@ua.edu

“Of Mice and Menthol: The Targeting of African Americans by the Tobacco Industry” is Copyrighted 2018

All of the items in Of Mice and Menthol: The Targeting of African Americans by the Tobacco Industry come from the collection of the University of Alabama Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society.

Contact

Alan Blum, M.D., Director

205-348-2886

ablum@ua.edu

© Copyright - The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society