When and Why the Anti-Smoking Movement Began

… It’s not what you think

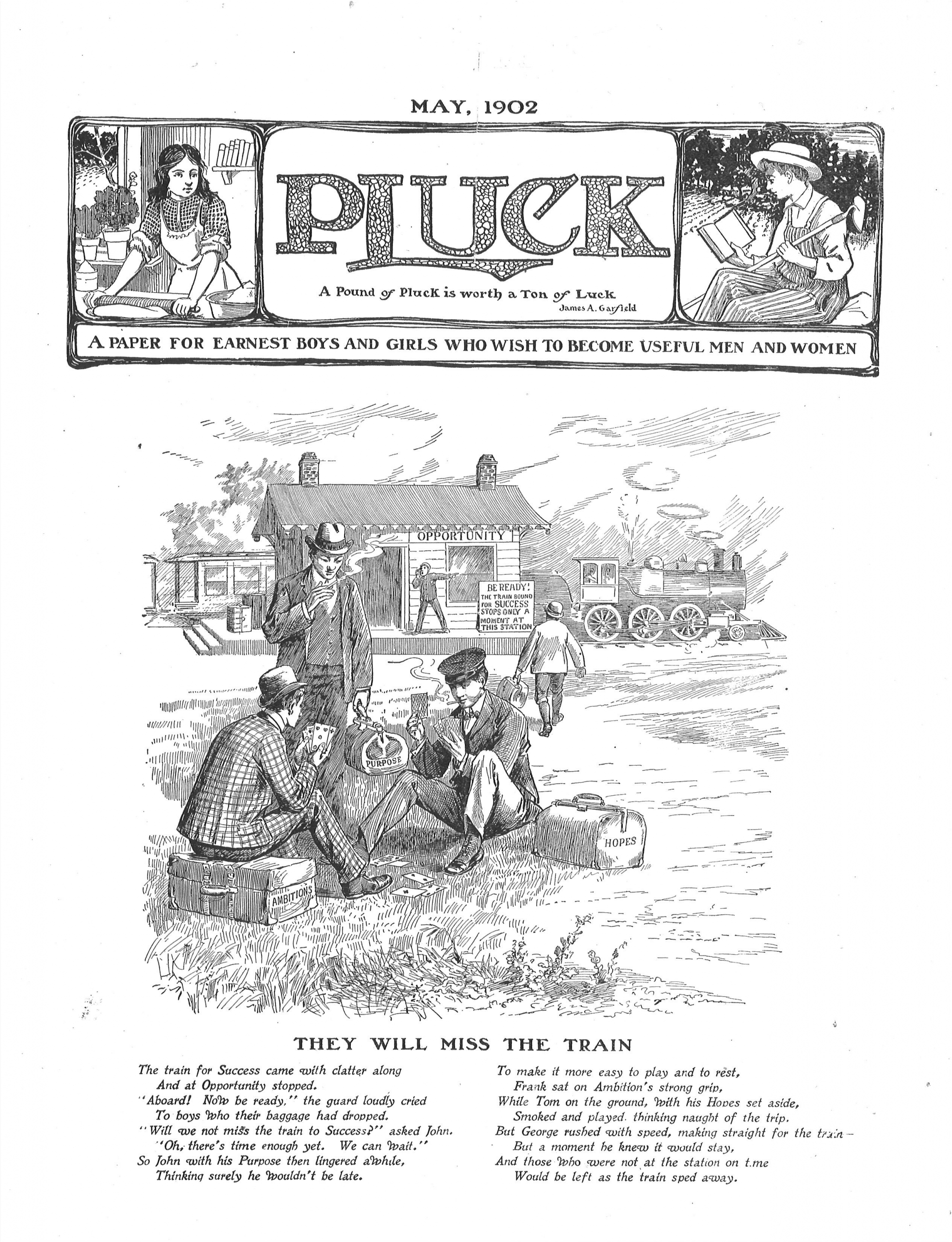

“The tumult surrounding tobacco’s damaging effects did not spontaneously arise in twentieth-century America. Contrary to the opinion of some, an anti-tobacco movement existed during the period of 1800 to 1870, with the first organized actions beginning in the 1830s, during a time of heightened reform activism in the United States. Periodical literature in that era contained numerous attacks on the pernicious weed. These reformers believed that there were agricultural, social, physical (health), and moral evils inherent in its production and use…” –Shane A. Smith, Ed.D.

Introduction

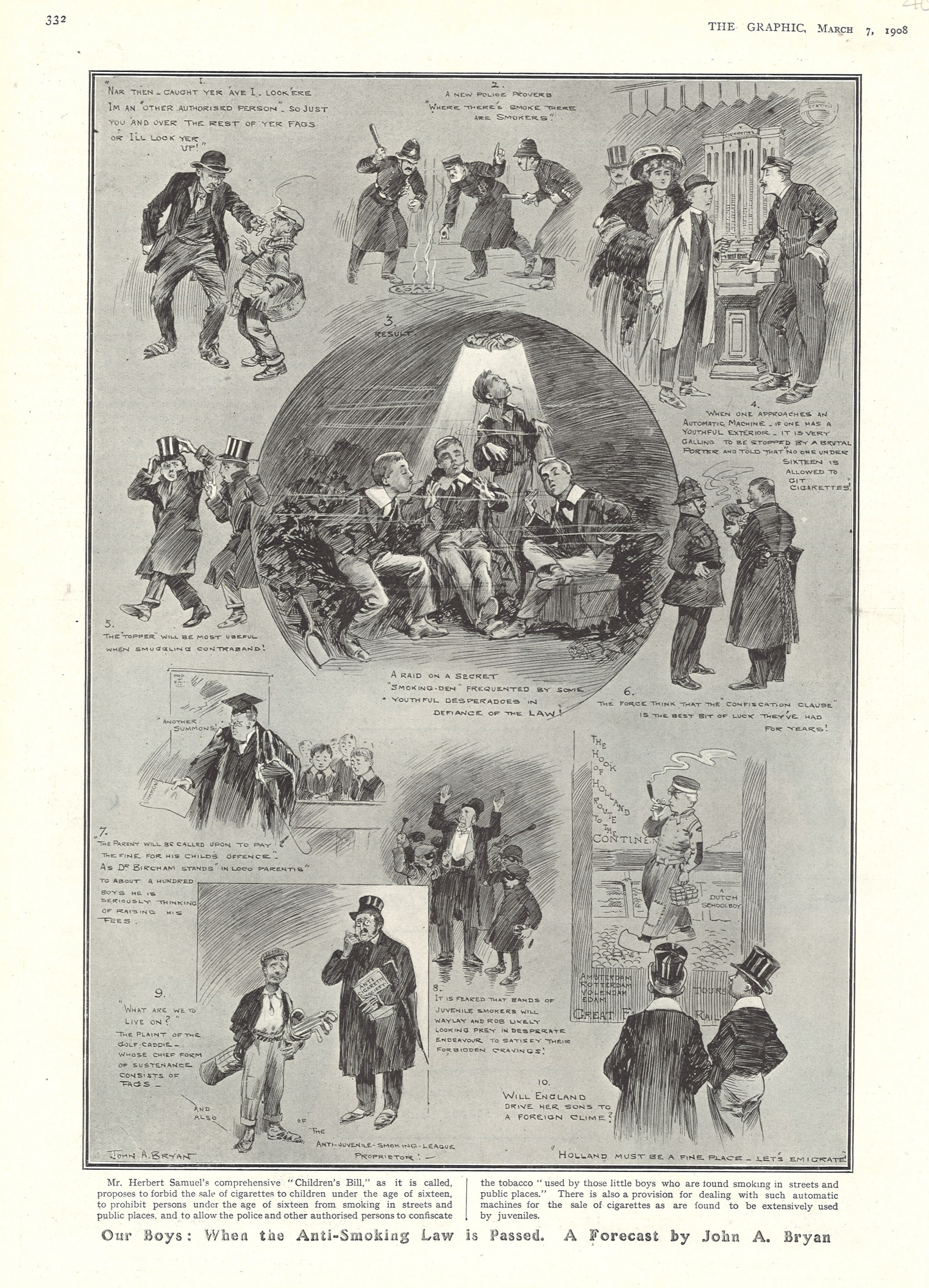

When I acquired the 16-page, March 1918 issue of The No-Tobacco Journal (“Official Organ of the No-Tobacco League of America”) 25 years ago, it seemed little different from the many other polemical anti-tobacco pamphlets and religious tracts from the mid-19th century and early-20th century in the Center’s collection. But coming across it again early this year, I did a double-take when I read the front-page heading, “For the Salvation of Our Boys – And the Race,” the advertisement on page 2 for a monthly magazine, Practical Eugenics, and the back-page ad for “Books on the Clean Life – Race Betterment.”

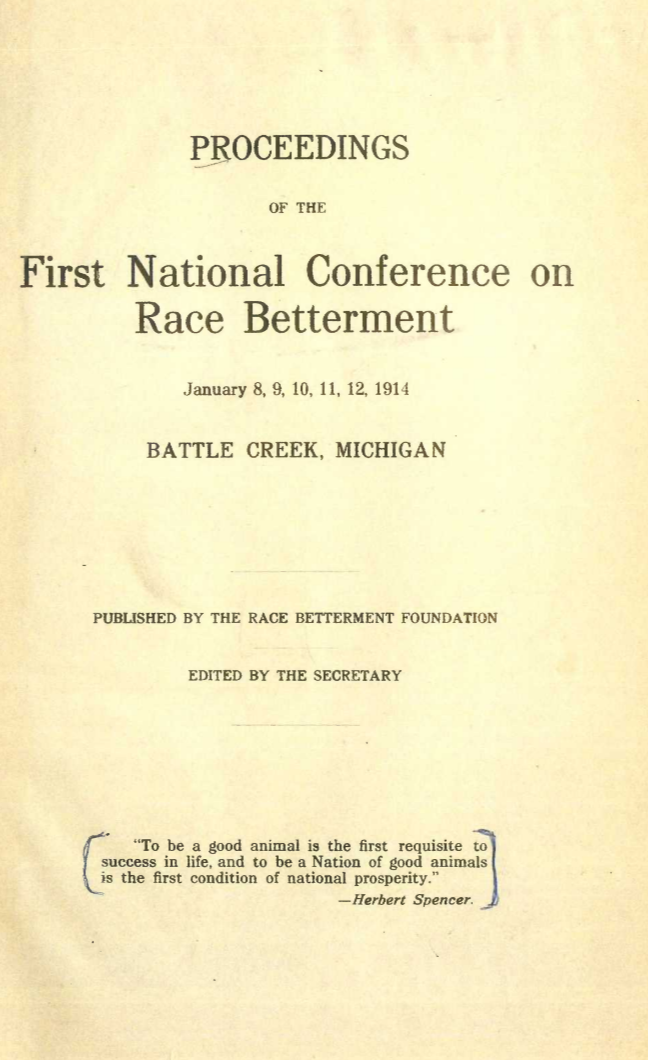

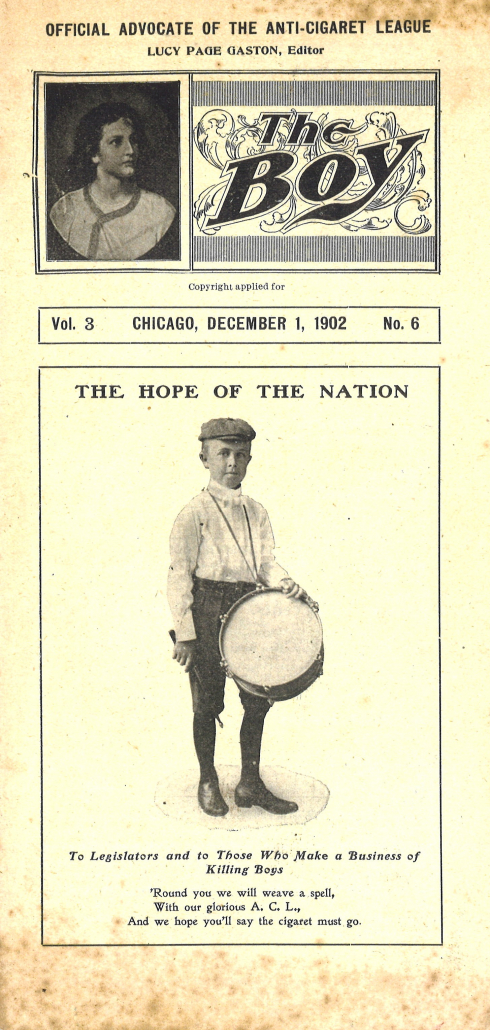

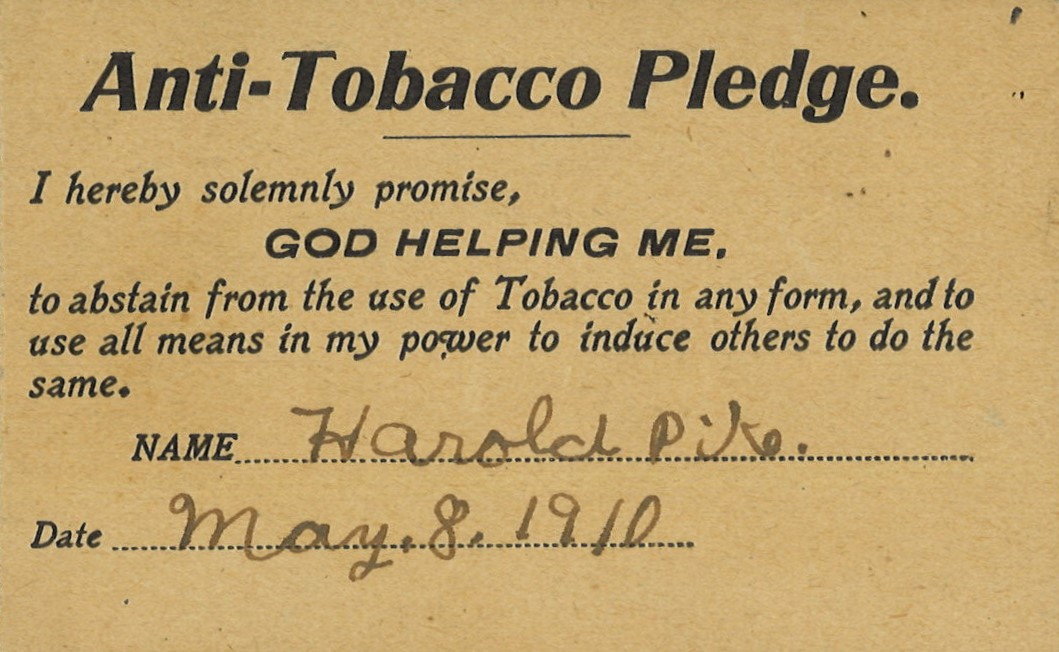

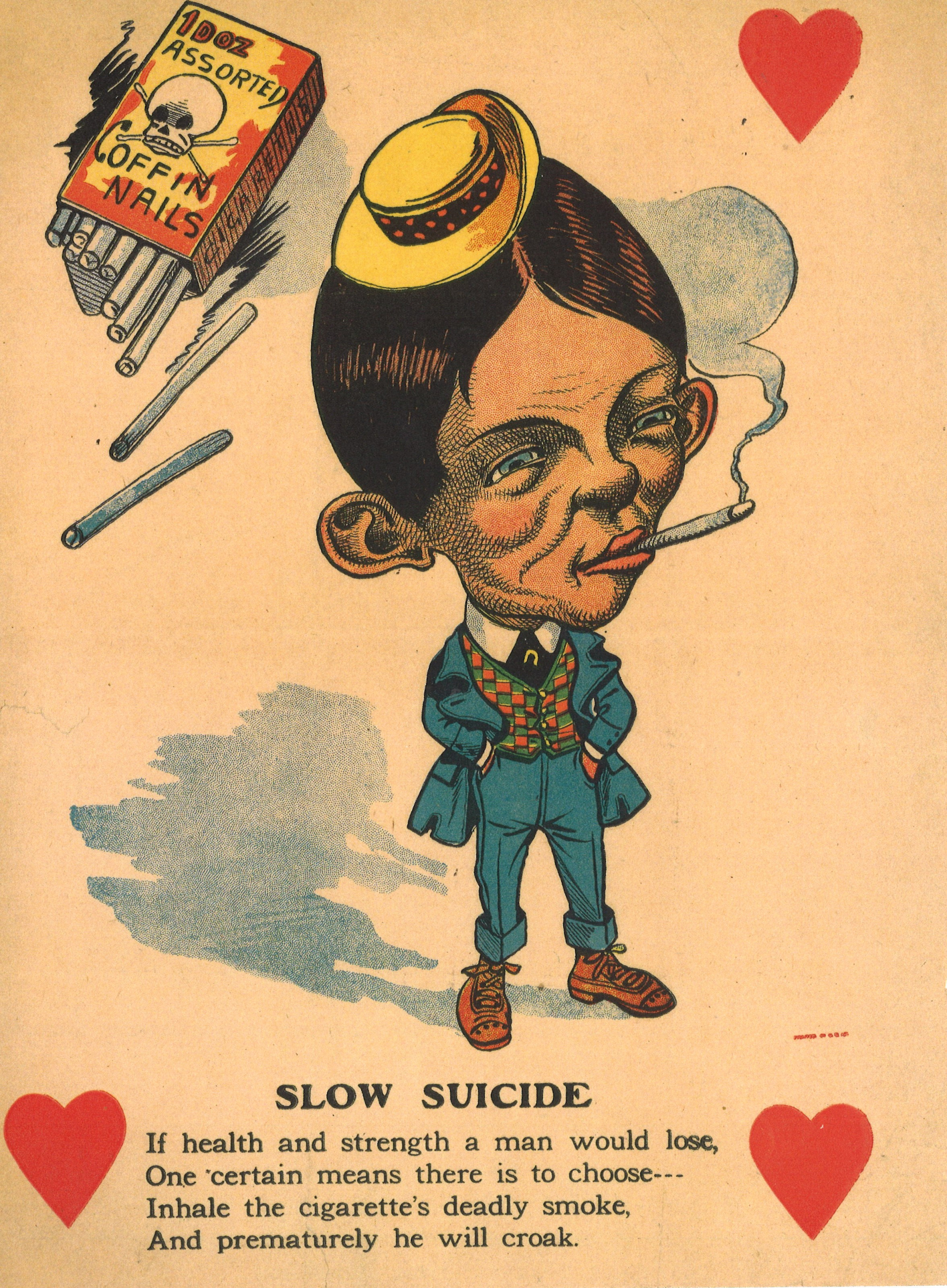

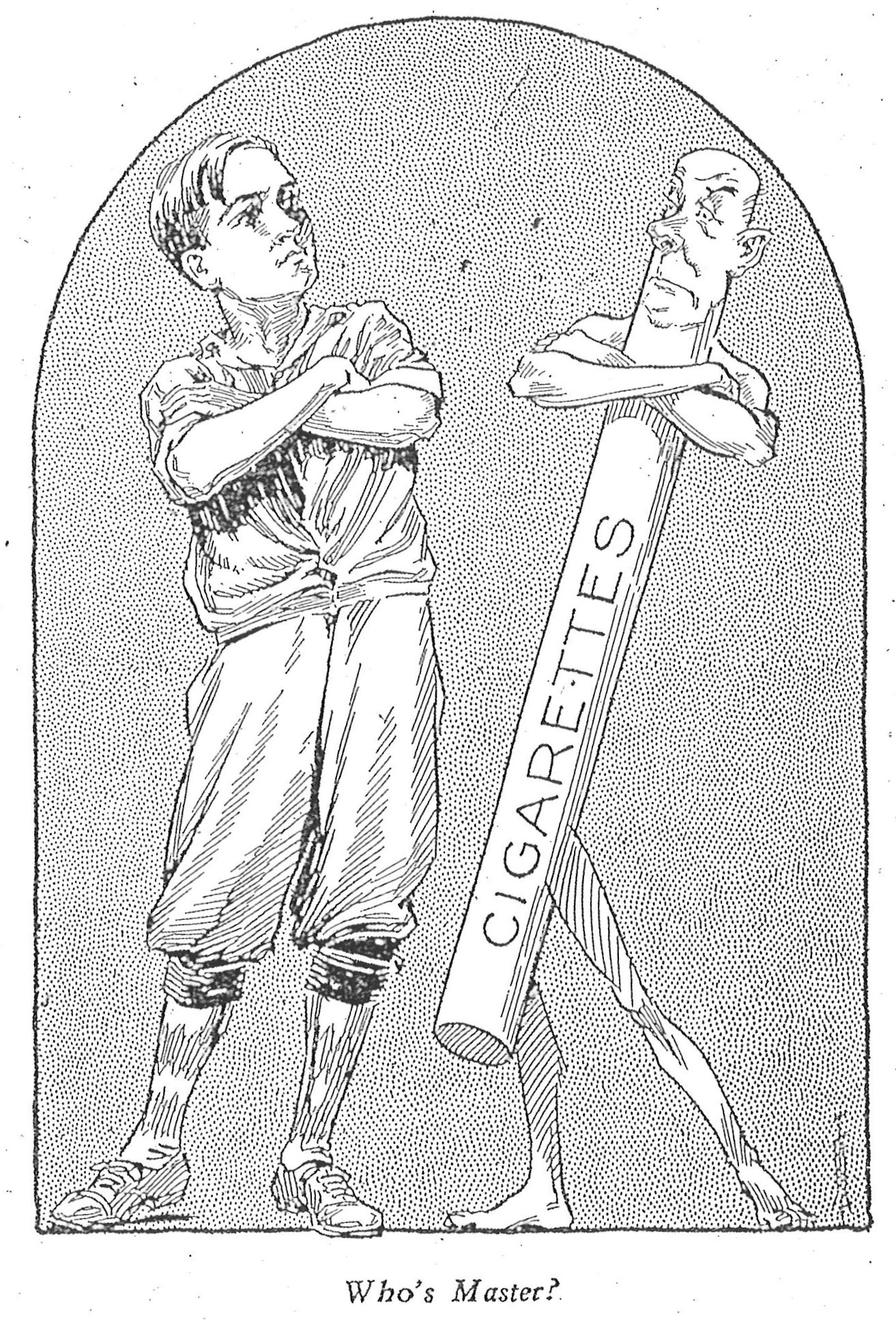

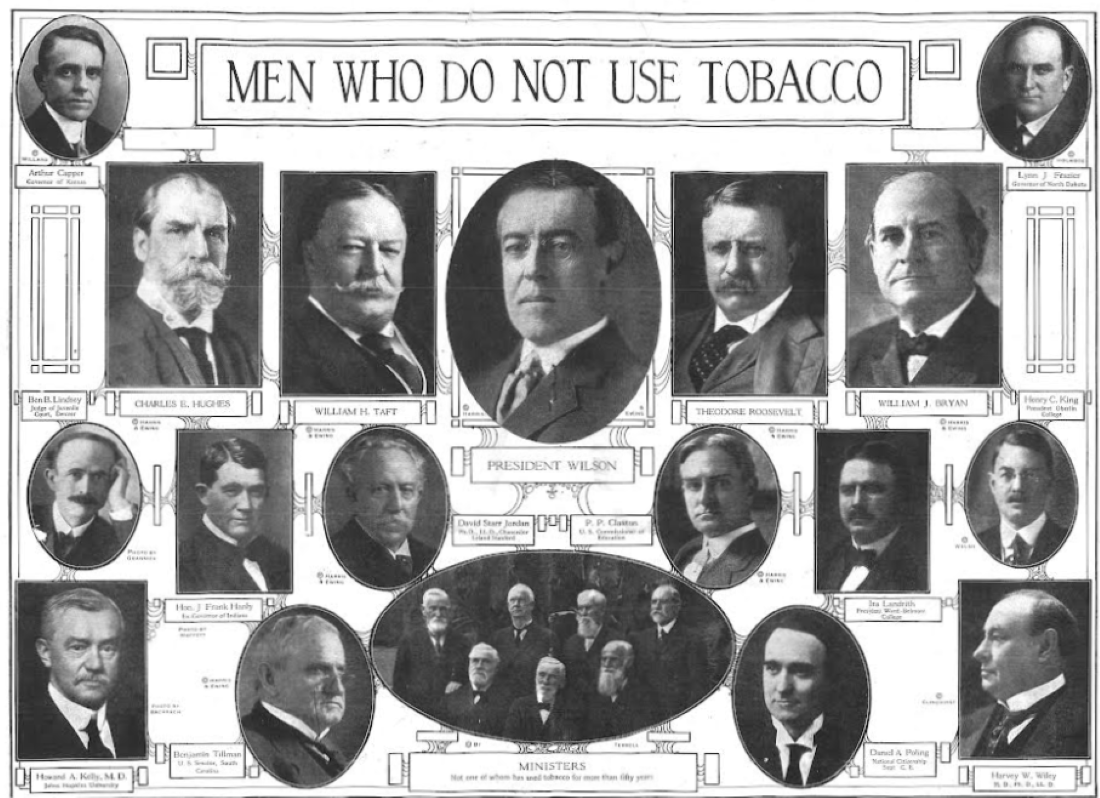

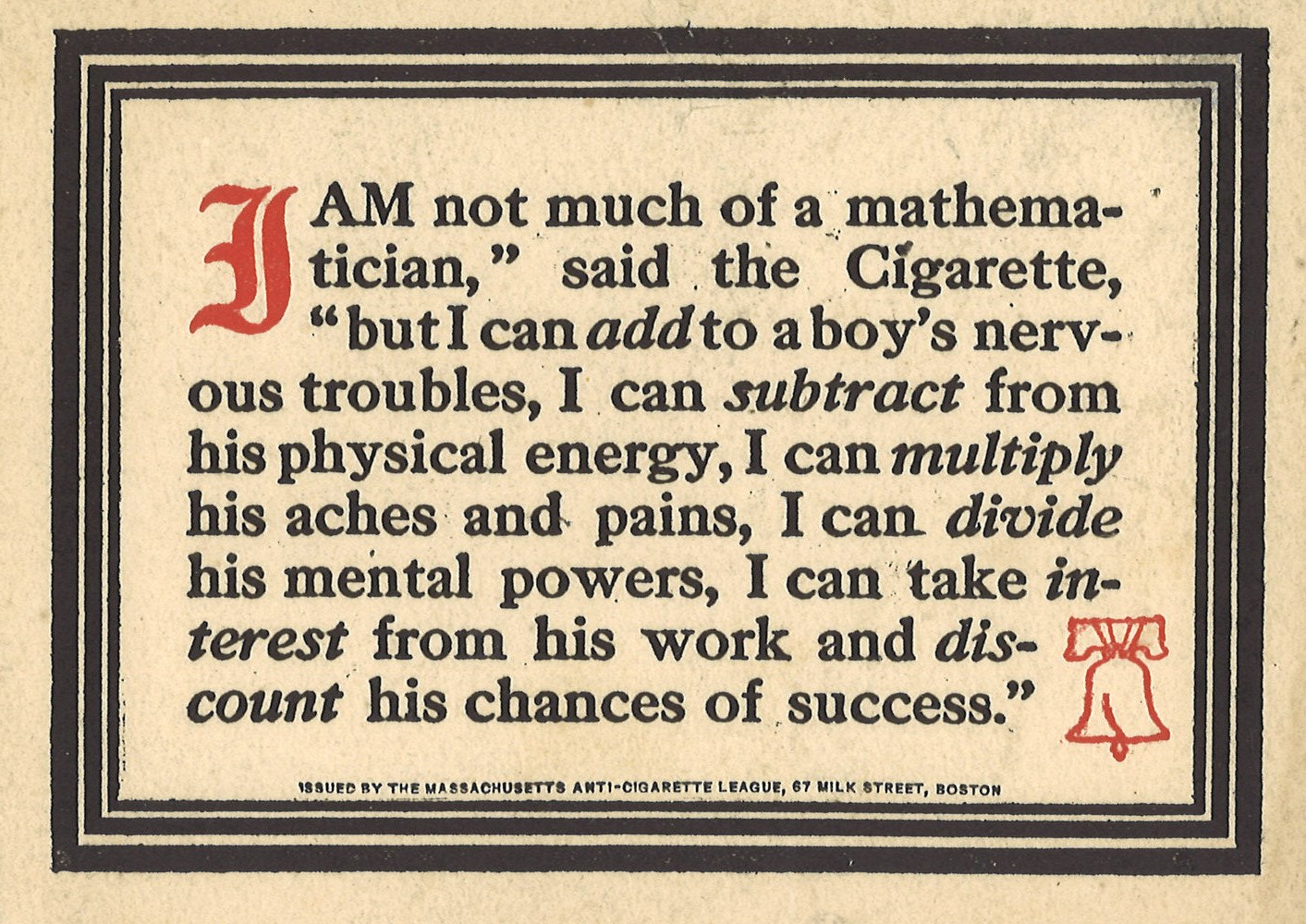

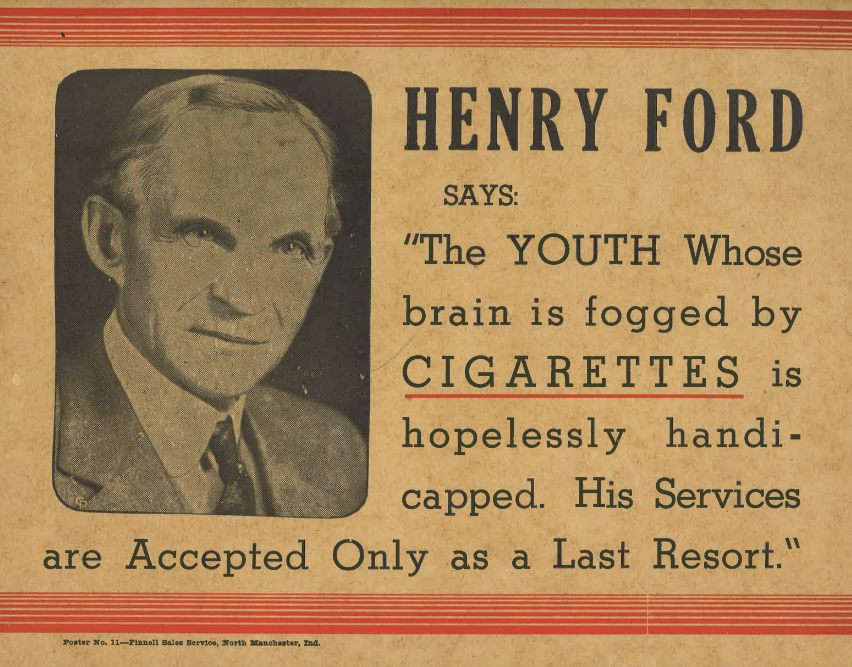

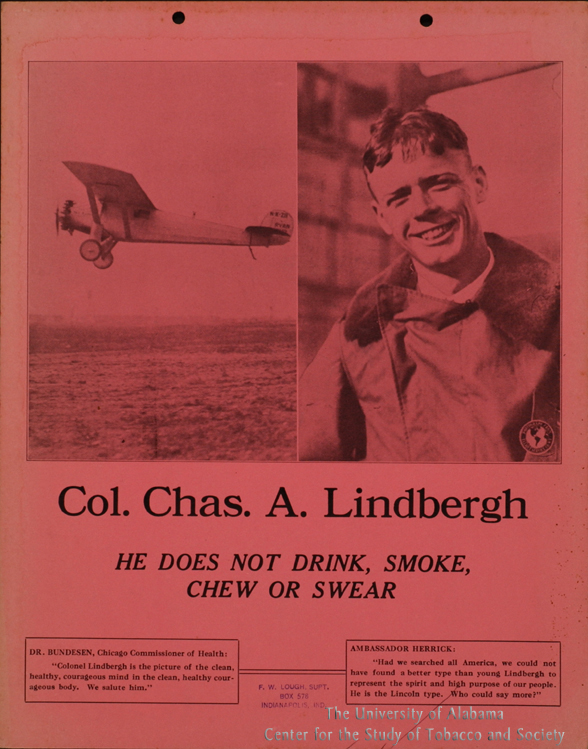

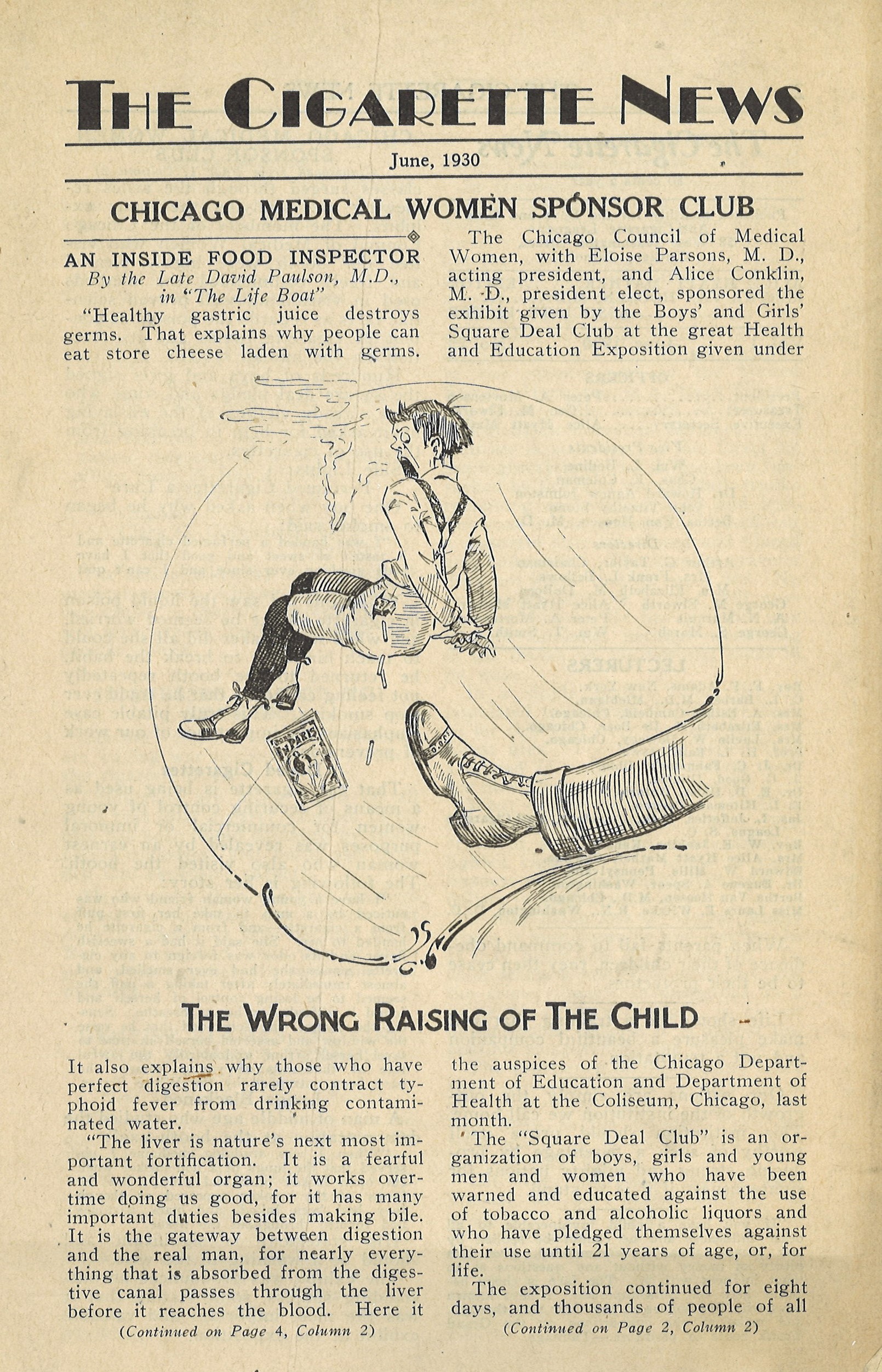

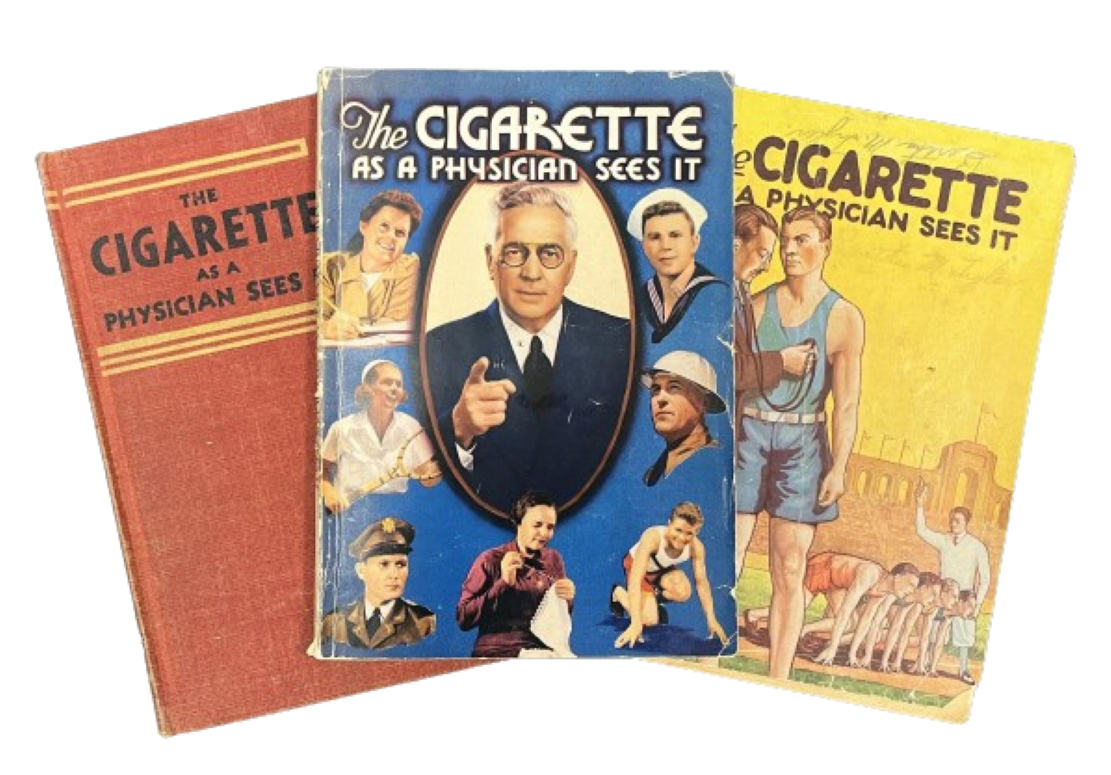

In our current era of political polarization, rising racism, and xenophobia, I wondered if the race-based eugenics* movement might have been one of the driving forces of the anti-cigarette crusades of the Progressive Era (1900-1930), so named because of its many social, political, and economic reforms. I was stunned to learn that Lucy Page Gaston (1860-1924), founder in 1899 of the Anti-Cigarette League of America (which would eventually claim 300,000 members), was a speaker at the First National Conference on Race Betterment in 1914, at which one presentation was entitled, “Tobacco: A Race Poison.” Several other public figures whose names appear on the mastheads of anti-cigarette newsletters were champions of forced sterilization and white supremacy. The American icons Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh were outspoken opponents of cigarettes – and even more outspoken proponents of antisemitism. This exhibition features examples of their anti-cigarette propaganda, as well as the fervent appeals and sermons of a variety of anti-tobacco organizations.

Ultimately – and fortunately – I have not found sufficient evidence to suggest that the connection between anti-smoking crusaders and proponents of eugenics represented more than an earnest quest for better health. Historian Jon Butler, Howard R. Lamar Professor Emeritus of American Studies, History, and Religious Studies at Yale University and a past president of the Organization of American Historians, agrees. “The eugenics movement we know most about was deeply patronized by liberal Protestants but had a very minimal connection to the anti-smoking movement.”

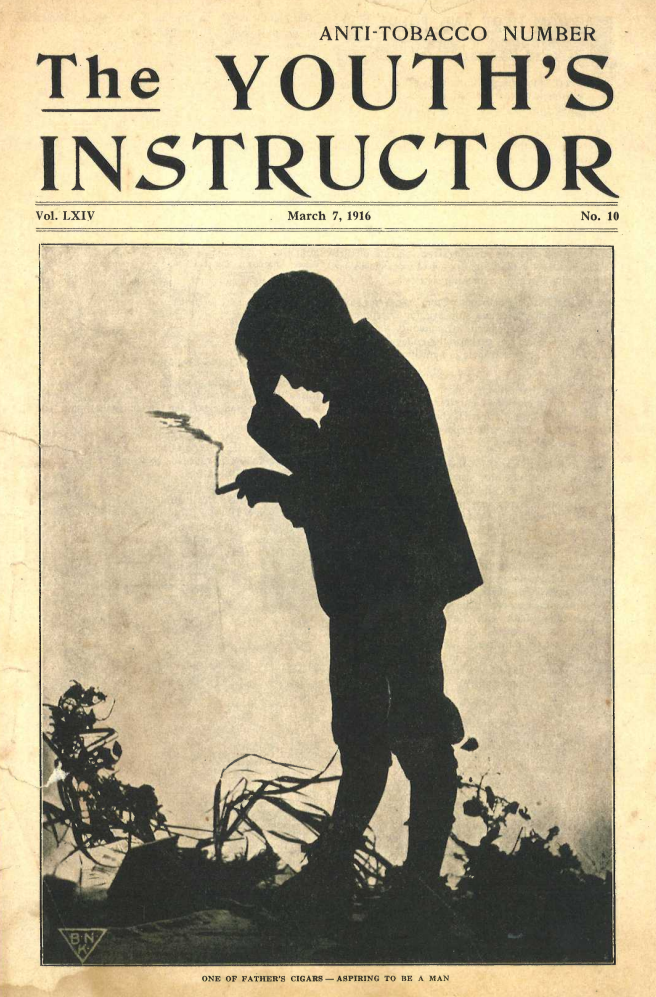

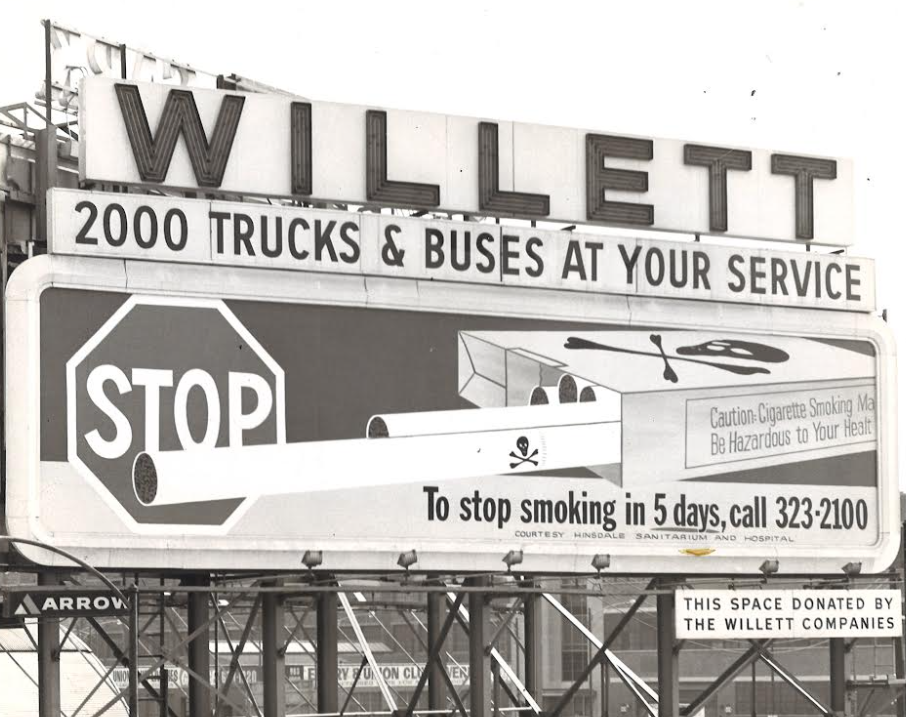

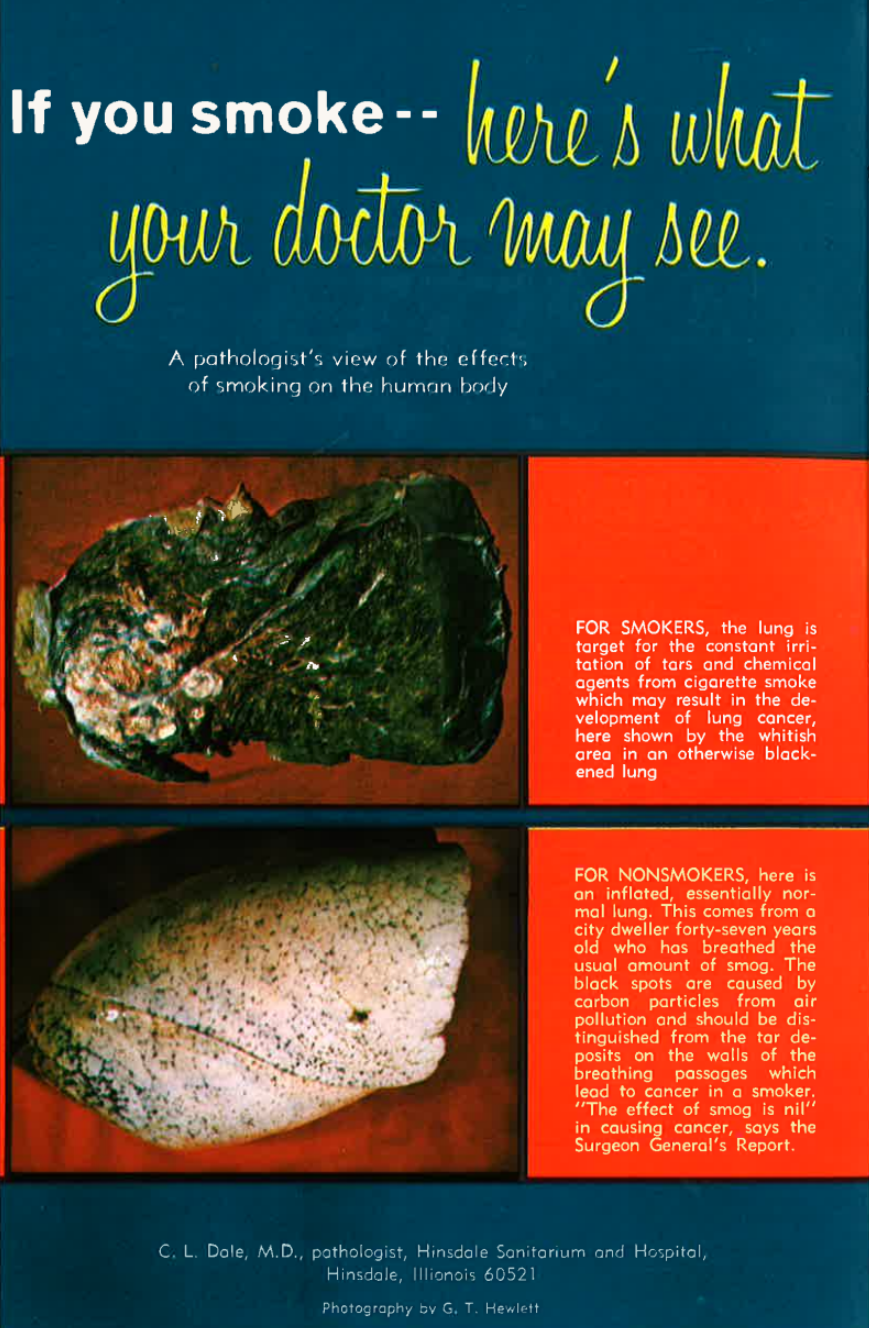

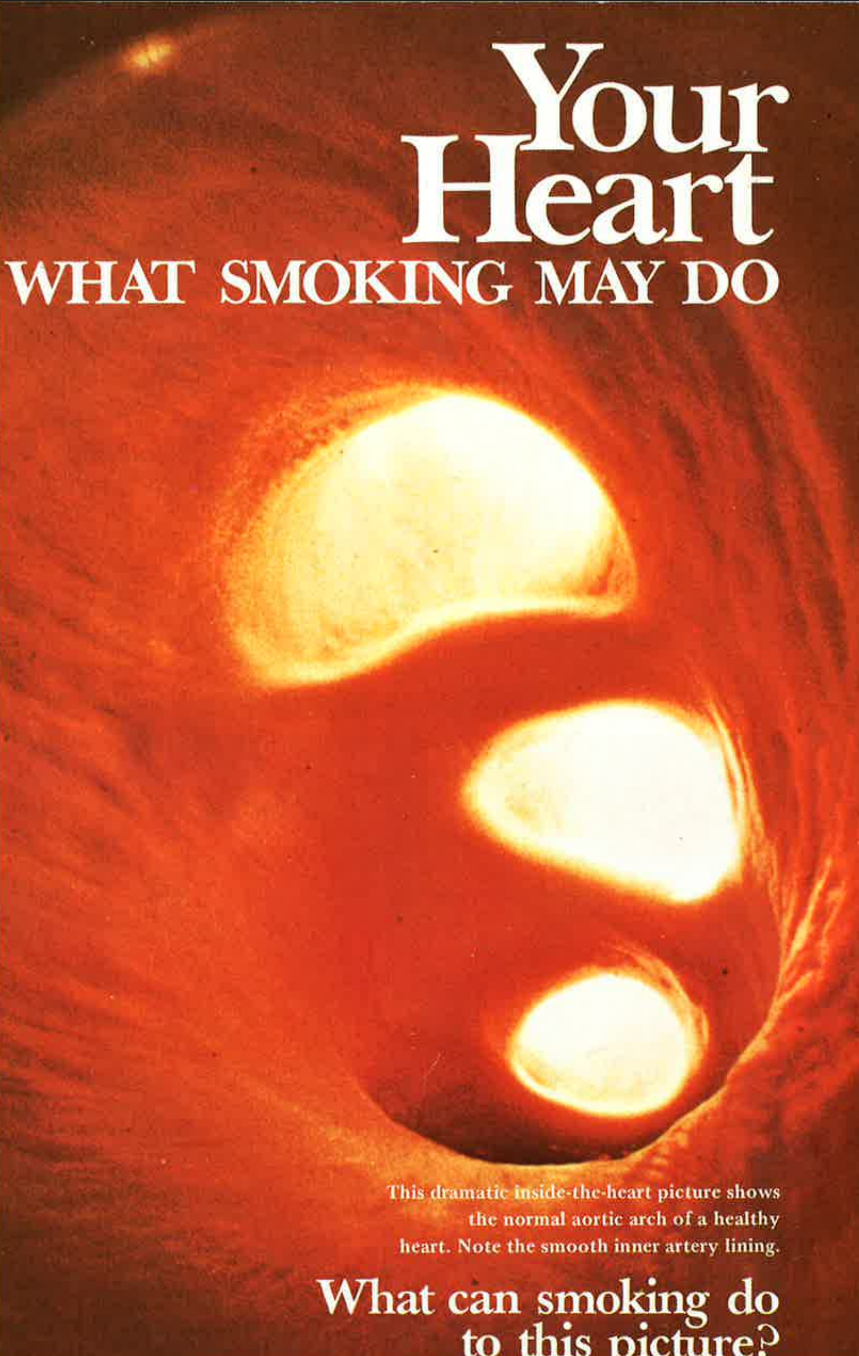

I had long assumed that the modern anti-smoking movement, which began in the 1960s, emanated from the accumulation of epidemiologic and pathologic evidence that indicted cigarette smoking as the leading avoidable cause of lung cancer and heart disease, as well as from the grassroots advocacy of individuals and groups for smoke-free restaurants, airlines, and other public places. But when all is said and done, the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists has led the way for more than a century in health-based appeals to give up smoking or to never start. The concluding portion of this exhibition highlights their efforts.

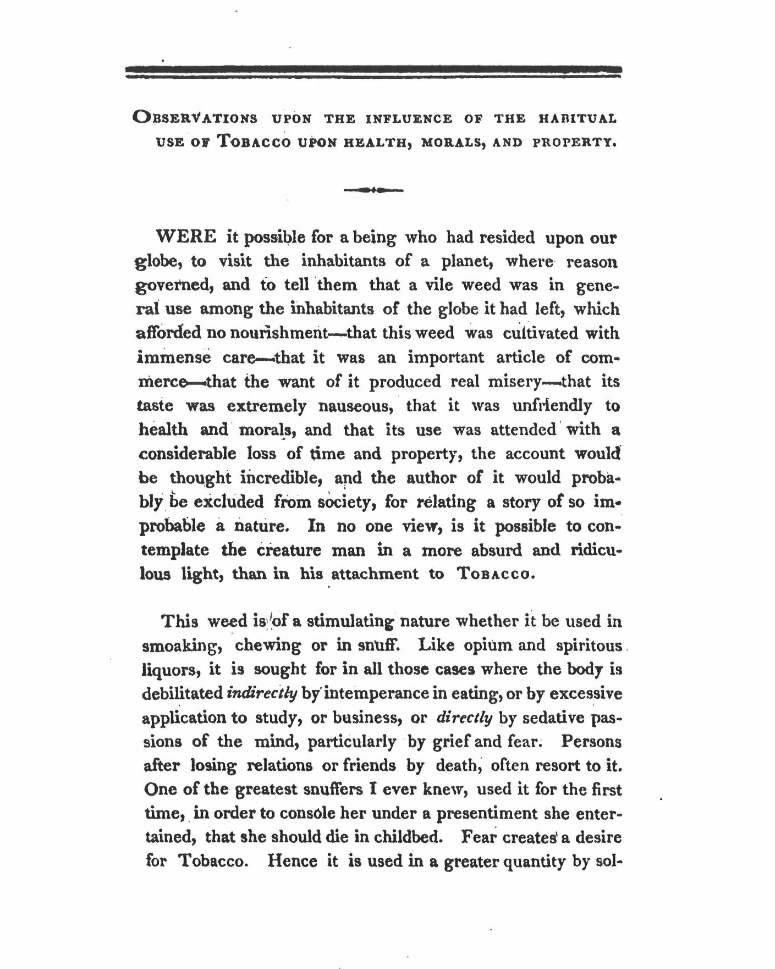

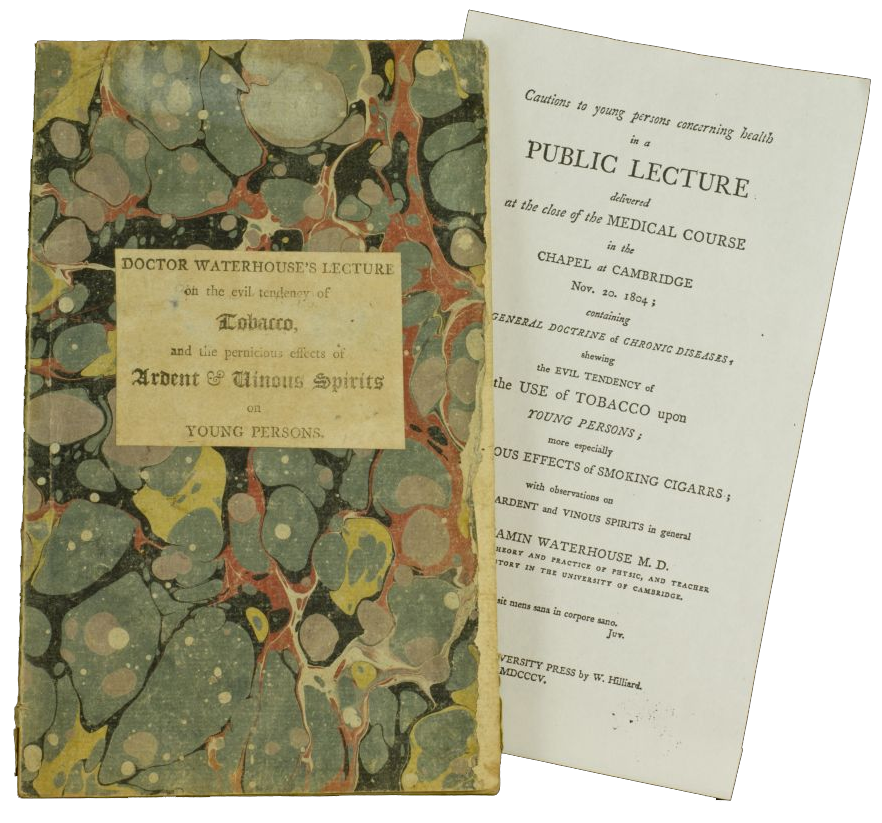

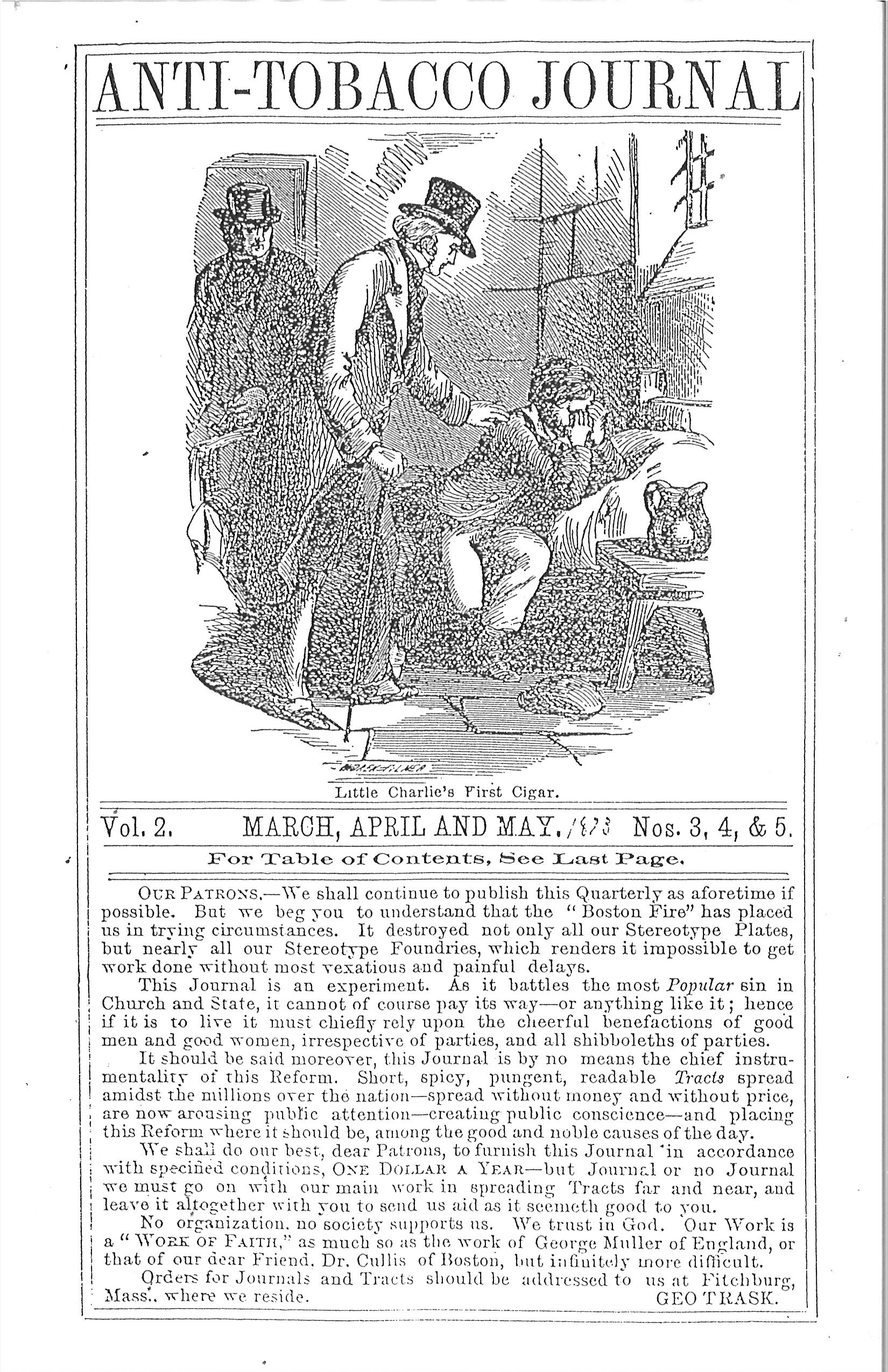

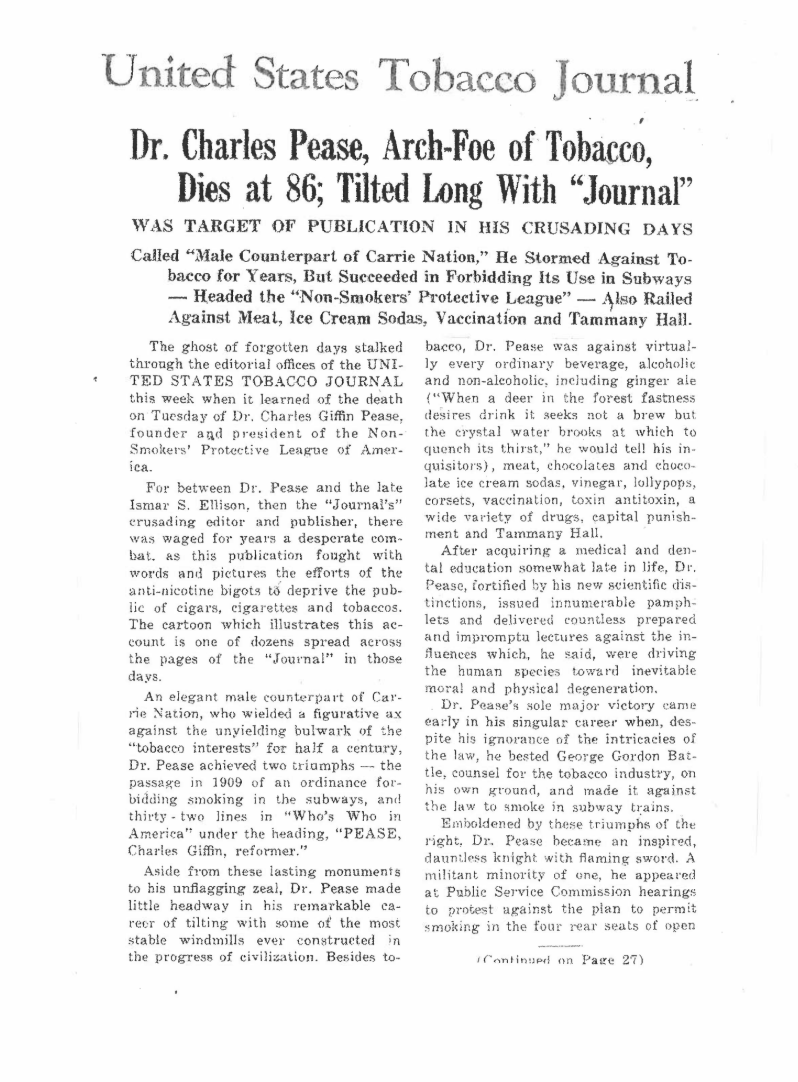

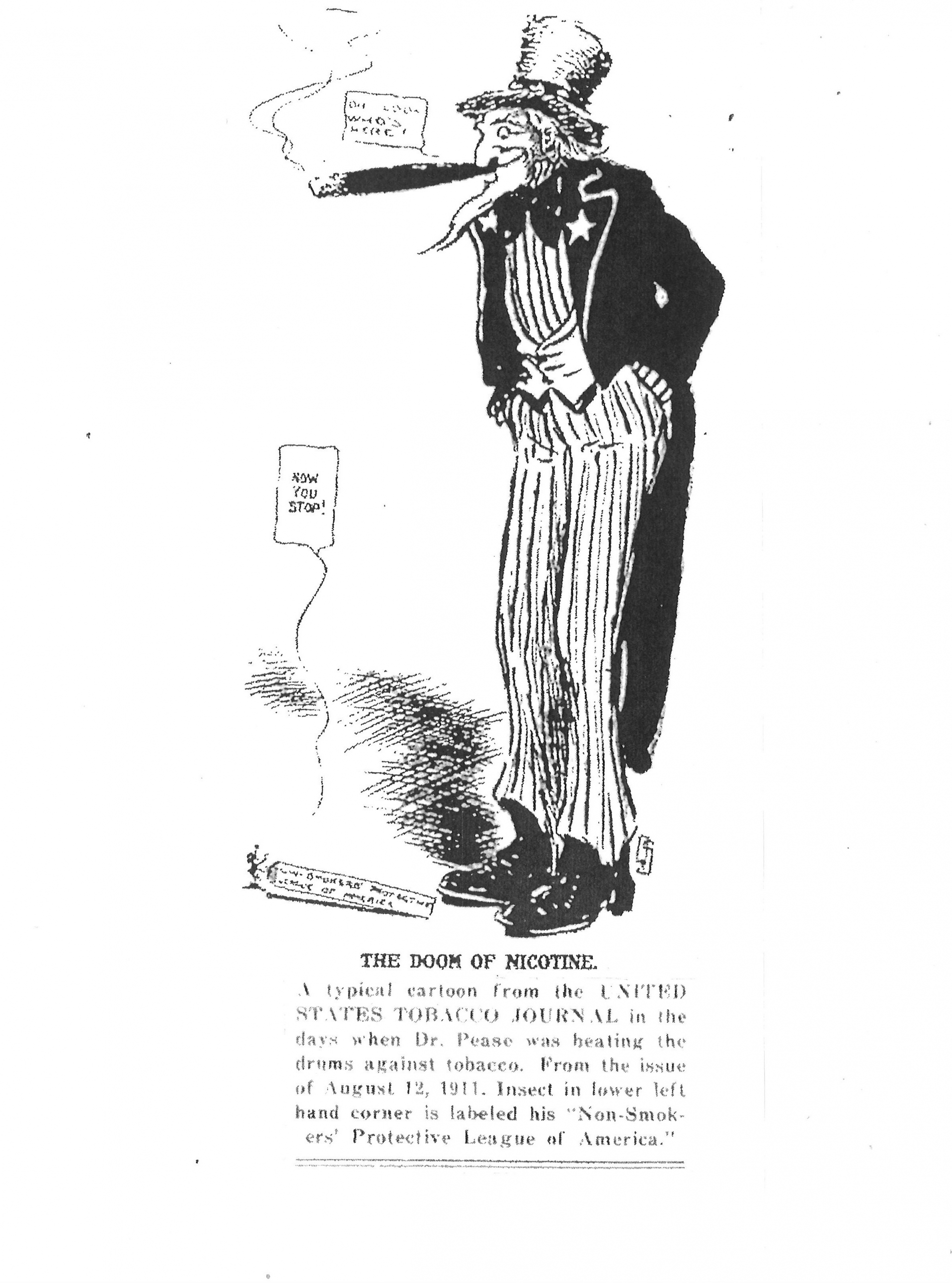

I had also believed that 19th century anti-tobacco advocacy consisted mostly of fulminations by religious zealots like the Reverend George Trask (1796-1865), publisher of the Anti-Tobacco Journal from 1857 to 1872. But the essay by historian Shane A. Smith, included in this exhibition, provides a corrective assessment. The 19th century arguments against tobacco were far more scientifically-based than we like to admit, especially those of agricultural experts. Perhaps the medical indictment of cigars and chewing tobacco by famed physicians Benjamin Rush and Benjamin Waterhouse was only partly accurate, but their entreaties to abjure the use of tobacco were written before the advent of cigarettes and the epidemic of lung cancer. Smith argues that 19th century opponents of tobacco were no slouches. His essay is essential reading.

Alan Blum, MD

Director, The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society

September 5, 2024

*The word “eugenics” was coined in 1883 by British scientist Francis Galton, a half-cousin of Charles Darwin. Galton believed that it was possible to produce a highly gifted race of men

through selective breeding, which he termed “positive eugenics.” Introduced in the United States in the 1890s, eugenics was well-received by educated Anglo-Saxon Protestants worried about the threat of the influx of eastern and southern European immigrants to “American stock.” Over the next 30 years, eugenics advocates succeeded in convincing legislatures in 24 states to pass laws mandating the sterilization of the mentally unfit. The most terrible legacy of eugenics policies was perpetrated by the Nazis against Jewish, Slavic, and Roma populations, as well as homosexuals and political dissidents. (Adapted from the catalogue of the exhibition “Perfecting mankind: Eugenics and Photography,” curated by Carol Squiers, International Center of Photography, New York, January 11-March 18, 2001)