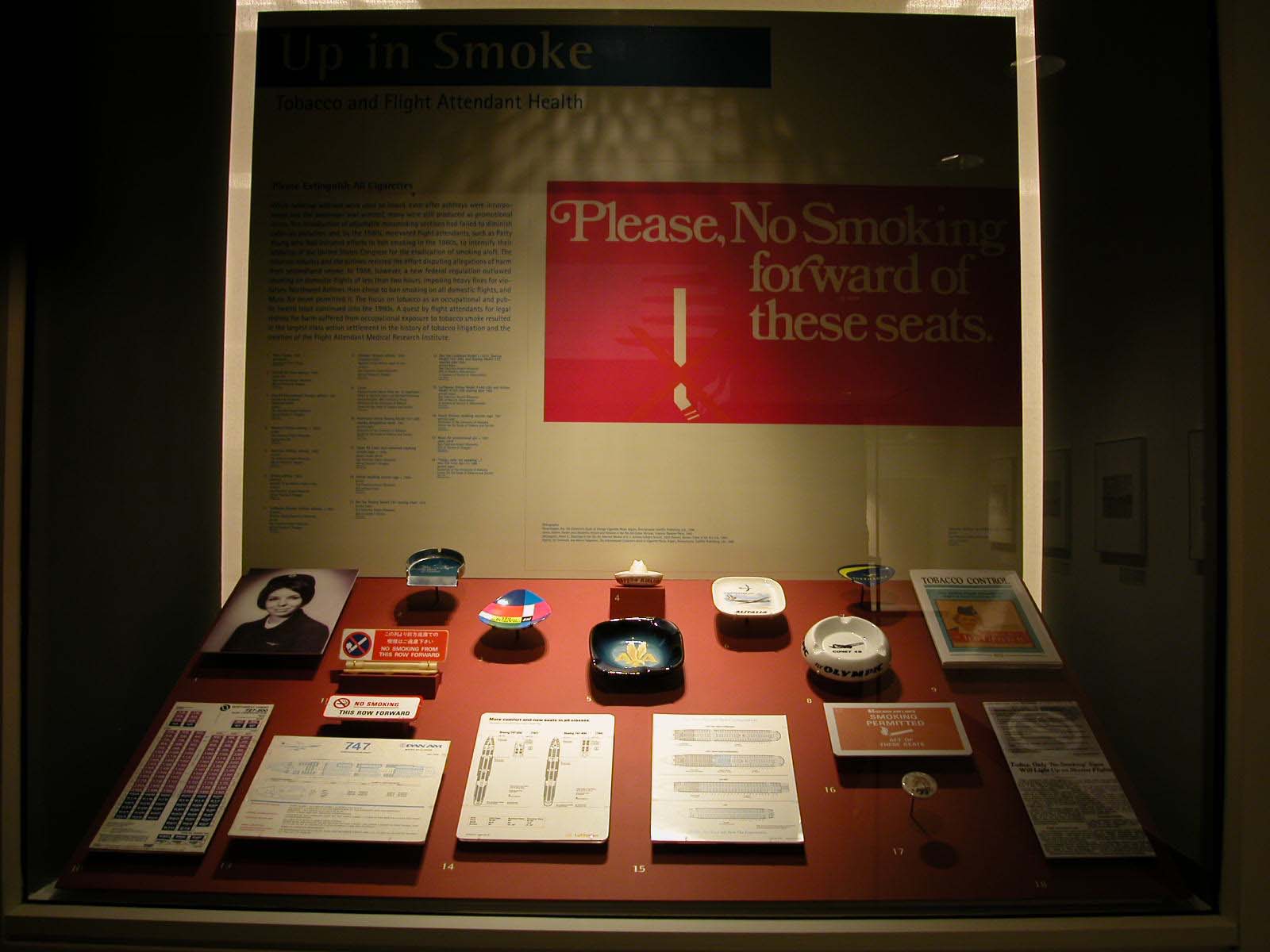

Up in Smoke

The Airline Flight Attendants’ Fight to End Smoking Aloft

Symposium

Case 1

Case 2

Case 3

Case 4

1926

1929

1931

1936

1930s

1939

1939

1940

1940

1940s

1940s

1940s

1947

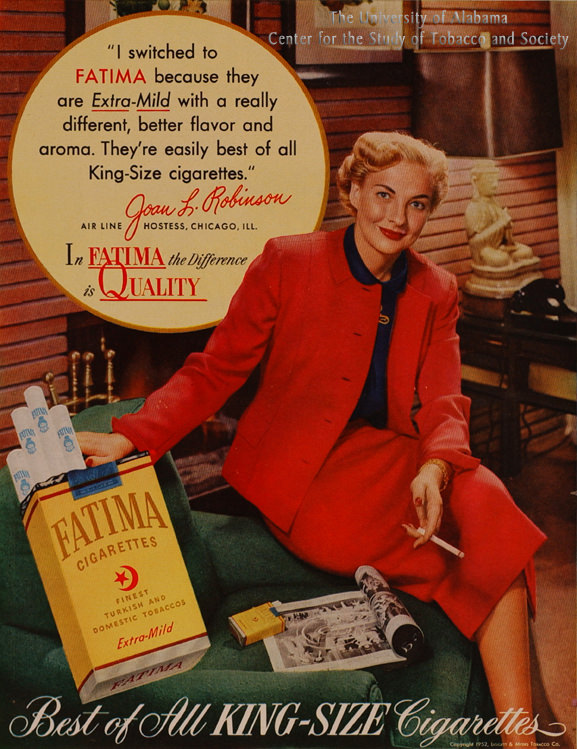

Air Hostess cigarettes 1950s

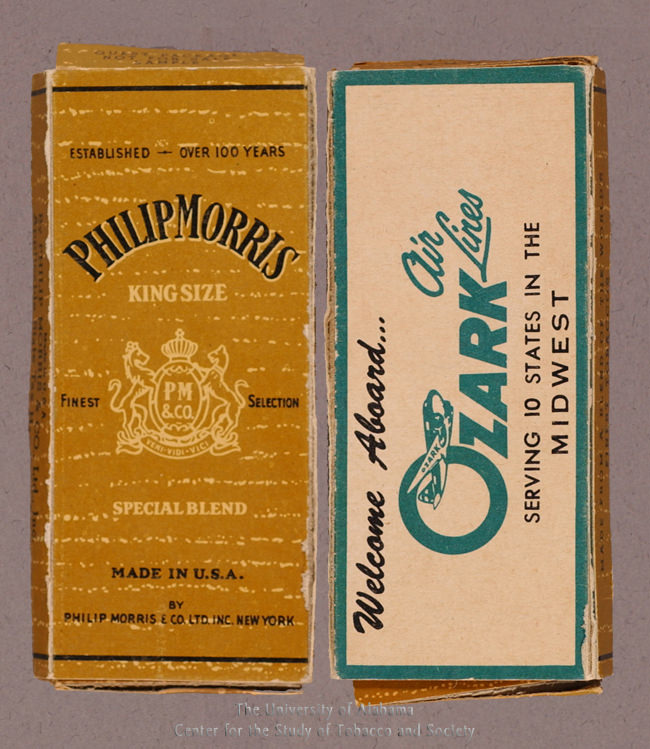

1950s, Free sample pack Phillip Morris cigarettes on Ozark Airlines

1952

1952

1960

1961

1963

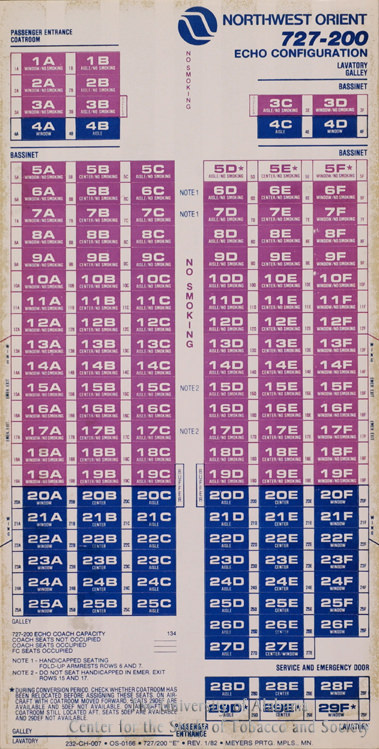

Seating chart 1982

1984

1985

1986

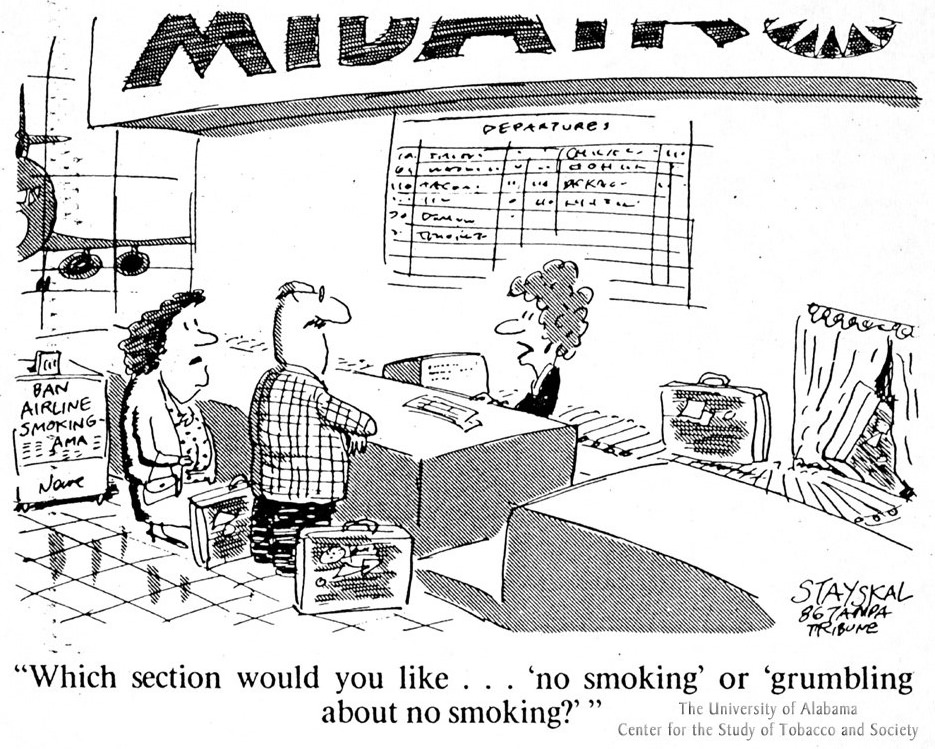

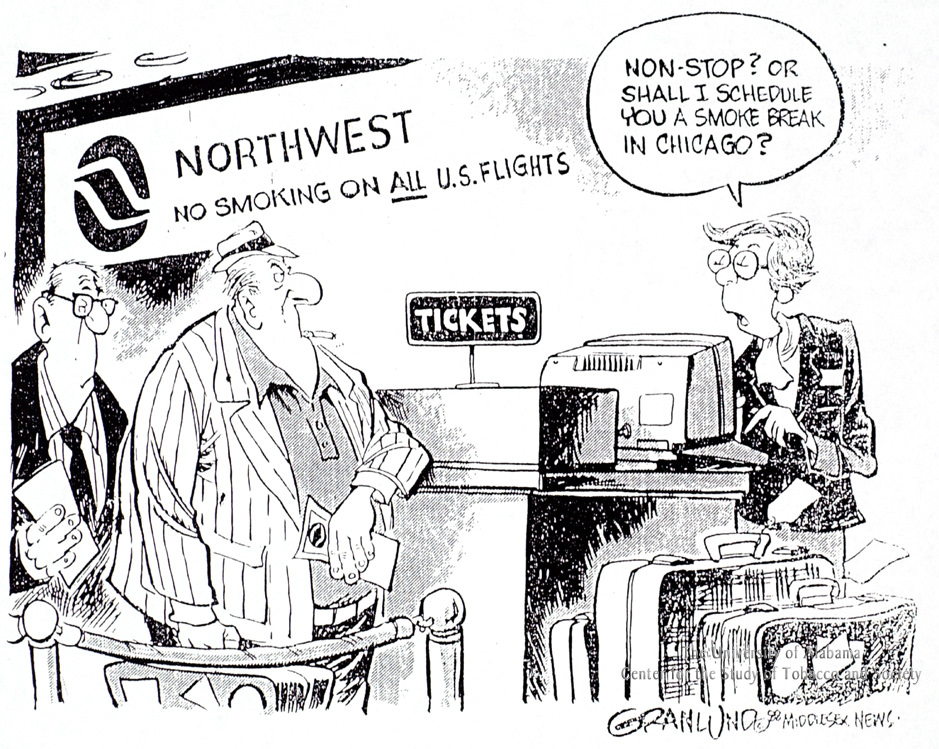

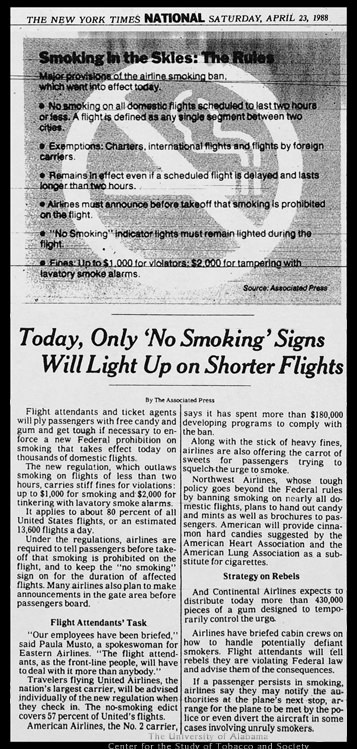

1988

1988

2002

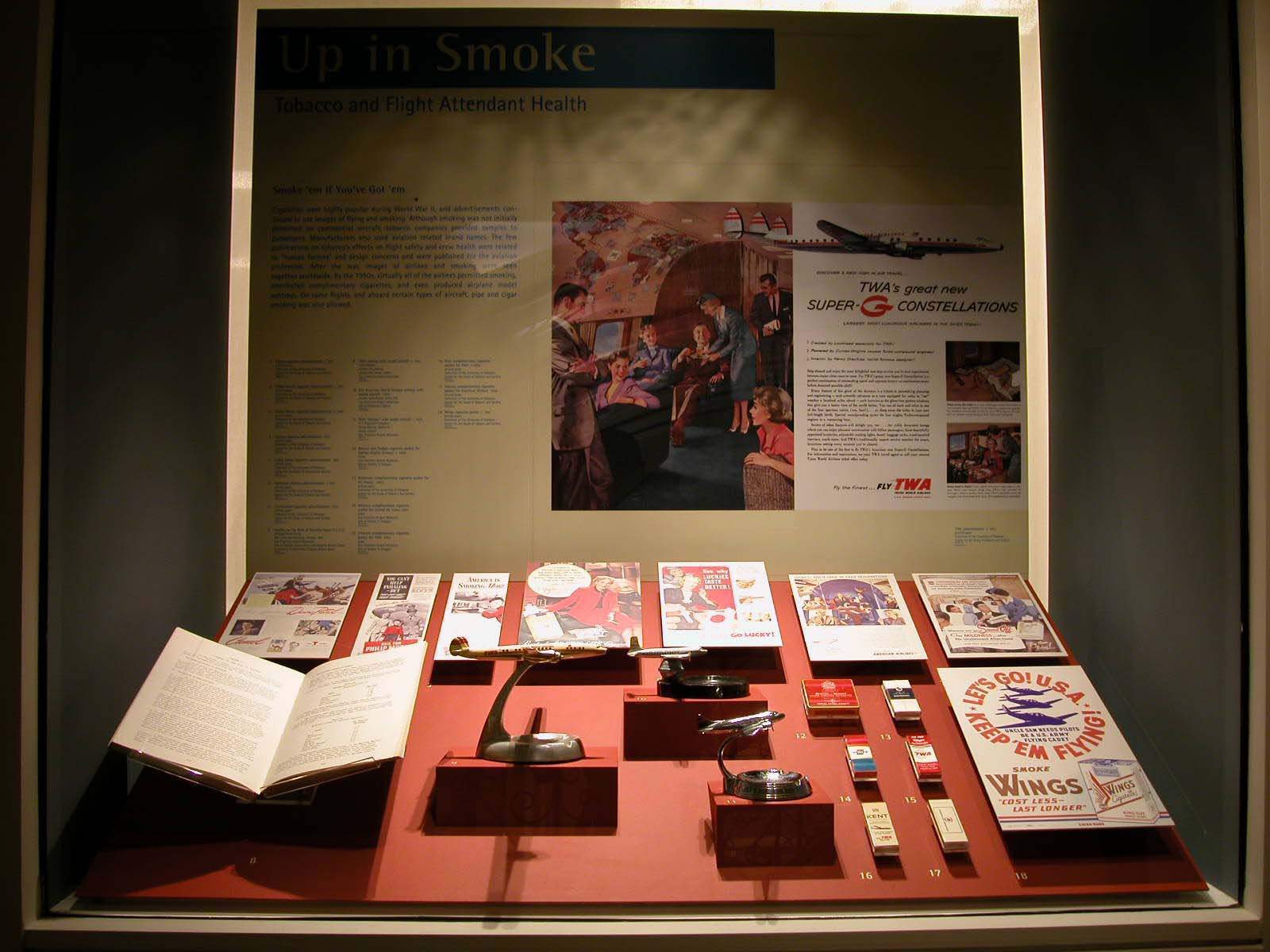

With support from the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, The University of Alabama Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society is conducting a comprehensive research project to document the history of smoking on commercial aircraft. This exhibit utilizes the collections of the Center to provide a glimpse of the imagery that helped foster the social acceptability of smoking aloft.

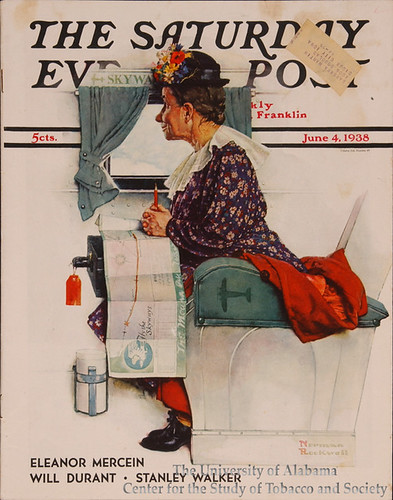

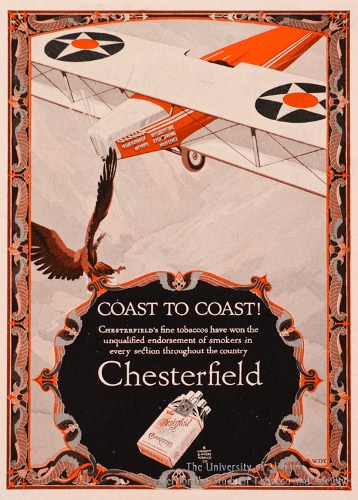

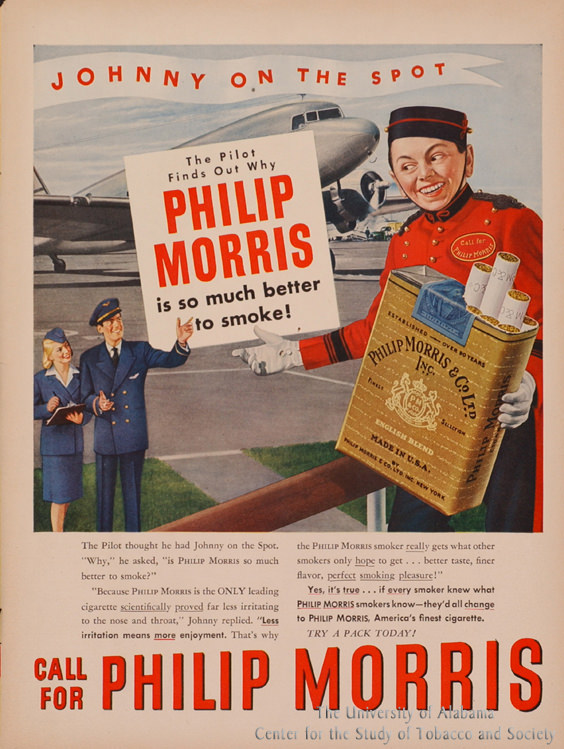

The emergence of civil aviation in the 1920’s and 1930’s was associated with glamour, daring and sophistication. At the same time, smoking was being promoted and popularized. The two industries were often depicted together in cigarette advertisements with an aviation theme.

Advertisers often linked women to smoking and flight, Images of aviators and aviatrices such as Amelia Earhart were invoked to sell cigarettes.

Cigarettes were very popular during World War II. Advertisements and posters from this time often depicted flying and smoking together. Although smoking was not initially permitted on airplanes, cigarettes companies provided sample packs to customers.

After the war, images of airlines and smoking were seen together world-wide. By the 1950’s, virtually all of the worlds airlines permitted smoking and distributed complimentary cigarettes.

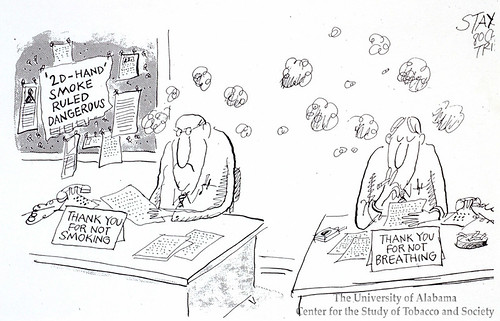

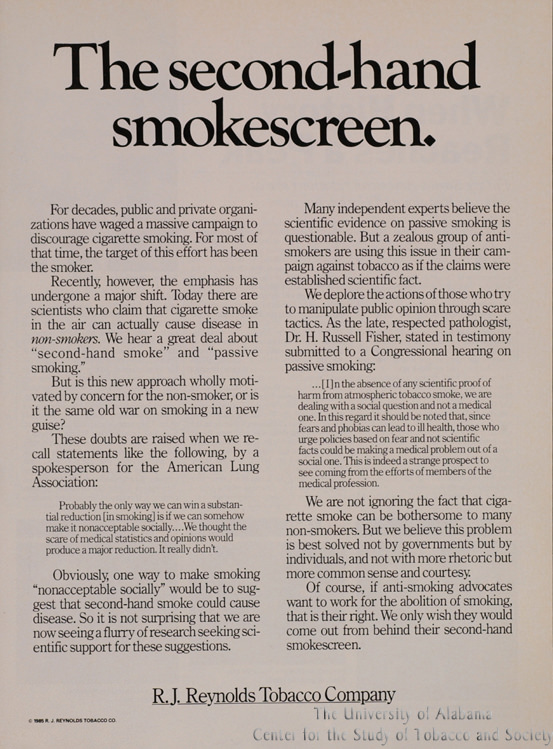

In spite of the growing recognition of the harmful effects of smoking in the 1960’s and 1970’s, airlines made little effort to protect non-smoking travelers. By the 1980’s, the failure of adjustable non-smoking sections to diminish cabin air pollution motivated a handful of flight attendants in the U.S. to lobby Congress for eradication of smoking aloft. The tobacco industry attempted to subvert these efforts by creating such terms as “Environmental Tobacco Smoke”, conducting bogus research, and dismissing allegations of harm from secondhand smoke as hysteria.

In the 1990’s the quest by flight attendants for legal redress for harm suffered from occupational exposure to tobacco smoke resulted in the largest class-action settlement in the history of tobacco litigation and the creation of the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute.

Canaries in the Mine: The Airline Flight Attendants’ Fight to End Smoking Aloft

An interview with four public health and safety pioneers

Introduction

In November 2002 Alan Blum, M.D., Director of The University of Alabama Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society, sat down with the four flight attendants who serve on the Board of the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, in order to learn about their personal occupational experiences in confronting the problems of exposure to tobacco smoke. The interview was transcribed by Lori Jacobi, M.A., Archivist, The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society, and edited by Dr. Blum for a special supplement of Tobacco Control. Various historical documents related to smoking on airplanes (from the Center’s collection, in italics) were shared with the flight attendants to facilitate the discussion.

Who We Are

Bland Lane:

I started flying fresh out of college for Pan American World Airways in 1954, and then in 1986 I transferred over to United Airlines, retiring in 2000.

Patty Young:

I’m 56. I started flying for American Airlines in the summer of 1966, after two years of college. In 1969 I started working to get smoking off the airplane and worked on it from ’69 through 1997 when it finally came off flights in the United States.

Leisa Sudderth:

I am 42 and in the 18th year of seniority with American Airlines. I grew up in a small town in Mississippi and graduated from the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg with a degree in communications. I started flying in 1985, and I fly international out of Dallas-Fort Worth. My activism on smoking began pretty much immediately. That’s how I met Patty.

Lani Blissard:

I grew up in Honolulu. I’m 56. When I first started flying in 1967, I was horrified at how dense the smoke was on the airplanes. I guess I was used to seeing smoke all over the place, because practically everyone smoked back then. But on this narrow metal tube it was so dense. We were told it’s a smoker’s right, and we really thought that smokers had their rights. We didn’t realize we had rights. And we were also told it doesn’t hurt you if you’re not a smoker.

How It All Started

“We do not encourage smoking aboard at any time, but it is permissible. Cigarette smoking only will be allowed, and pipes and cigars are prohibited. We must be very discreet in subjects of this kind. The greatest care must be exercised regarding lighted cigarettes and matches. Fire aboard is our worst possible hazard. Be sure that matches are well out and put only on metal containers for the purpose, and lighted cigarettes should be personally crunched to extinction. Stewardesses should be on the alert at all times regarding any possible fire hazard.”

Stewardess Circular No. 1, Boeing Air Transport (United Airlines), May 15, 1930

From a 1957 brochure, Welcome Aboard. American Airlines, America’s leading airline: “Nobody ever knew how passengers felt about smoking in flight until we conducted an opinion poll on the subject. We learned that most passengers have no objection to cigarettes but many find the smoke of pipes and cigars objectionable.

Those of us accustomed to smoking pipes and cigars are so used to them that we seldom think of how they affect fellow passengers, but pipe tobacco and cigar smoke is usually heavier than cigarette smoke, and an airplane cabin, despite the fine ventilation system, is not a large room.

Cigarette smoke irritates few persons. The smoke of pipes and cigars irritates many. In the interest of making this journey an enjoyable one for all, it is requested that you wait awhile for that cigar or pipeful, except aboard DC6 and DC7 flagships or DC7 air coaches where it is perfectly all right to smoke a pipe or cigar in the lounge. But go right ahead and smoke your favorite cigarettes anywhere in the cabin.”

Sudderth:

Being fresh on the airplane, when you’re brand spanking new, you’re just so proud to put that uniform on, and you just pinch yourself because you’re so lucky to be there. And then that “No Smoking” sign went off, and I went, “What is this? I didn’t sign up for this!” And, “brand spanking new” means you don’t complain about anything. You’re just happy to be there.

Young:

I was 19 when I went through training and 20 when I started flying that same week. I worked in the kitchen the vast majority of the time, and I started getting violently ill my first few months of flying. I would get so sick I was vomiting on my flights because of the headaches. The headaches hurt so bad they would make me get sick all over. Obviously I’d have to wash my face. I’d come back out and I’d work meals, but I was always standing right under a return air vent above my head that pulled all the smoke right past my face. I would wipe my face with a Kleenex because my eyes were watering and burning all the time. It always looked like I was wiping up a coffee stain, and it was the nicotine. My tears were the color of coffee, and my mucous was the color of coffee. That’s how much tobacco smoke went past my face and my body to get to that vent.

Know how mechanics used to check for any leaks in the aircraft? Any little crack in a window could be spotted because there’d be a brownish-green stain around it—a nicotine stain. Not just on the glass, the whole airplane. Even on the skin of the plane.

Sudderth:

As a new hire flight attendant, you’re on probation, you don’t want to make any waves, you don’t want to upset anybody, you don’t want to complain because you want to keep your job and you don’t want to draw attention to yourself. I was fairly new and I was helping an elderly man, just as frail as he could be, get on board before everybody else. I was leading him to his seat. When I looked at his ticket, I said, “Oh, this must be a mistake. I need to change your seat. They put you way in the back, in the Smoking section.” I said, “Let me change you so you don’t have to walk all the way to the back of the airplane. I’ll put you in the first row of the cabin. He said, “Oh no. I’m a smoker.” As soon as that No Smoking sign went off he was the first one to light up. Out in the waiting area he had had his own oxygen tank, so I just knew it must have been a mistake. I was stunned, absolutely stunned.

Young:

In my experience, the airlines themselves have never cared about health and safety on the planes, not in any form, shape or manner.

Sudderth:

I was horrified when these guys told me that they used to have to go through the cabin with cigarettes on a tray. I’ve never seen that.

Lane:

I hated having to dispense cigarettes.

Sudderth:

You didn’t have a choice

From a 1932 advertisement: “Smoke a fresh cigarette. Fresh cigarettes are now served in the skies. Camels are never parched or toasted. Last year 43,000 men and women flew to their destinations in the great planes of United Air Lines which travel more than a million miles per month. This year, to add to the pleasures of air travel, passengers on this line are served Camel cigarettes. Made fresh and kept fresh. Never parched or toasted.”

Lane:

They were little 4-cigarette packs.

Blissard:

On American Airlines, we used to give those away all the time.

Lane:

We had four different kinds of cigarettes. We’d line up the matches, which had the Pan Am logos on the matches, and then we’d line up the cigarettes and we’d go through the cabin row by row.

Young:

I didn’t realize the extent of how the tobacco industry used the airlines.

Lane:

Neither did I. I saw ads here and there, but I wasn’t a smoker. I never even read them.

Smoking Section

Lane:

When they started the No Smoking zones, Pan Am tried everything. They tried, first of all, to put smokers in the back, then the smokers in the front. Then they tried one side, then the other. And then they said if you get one smoker in the row, the whole row is smoking. The only thing you had was a little sign you put on the back of the seat. As far back as they got selling seats to smokers would be the smoking section. It ended up with non-smoking in front. They tried both ways. Two or three months this way, and then they’d get too many complaints so they would try something else. Every flight was different. Going to Japan we would have 200 passengers in economy. The first two rows were non-smoking. All the rest were smoking.

From (British) Imperial Airways Gazette, April 1936: “A few remarks about smoking. By the way, this brings up another point that I have heard discussed, and that is the matter of smoking. I mention this, as I am a very heavy smoker myself and consume well over a tin of 50 cigarettes per day, and had been rather chaffed regarding the rule of “Non-Smoking” on aeroplanes. As a matter of fact, the comparative strangeness, combined with the knowledge that I must not smoke, seemed to make smoking rather far in the distance, and it didn’t worry me at all, although I must admit that I would have liked a cigarette at the time I finished breakfast on the plane. However, the aeroplane invariably comes down every 3 or 4 hours for re-fueling, and as this takes about a quarter of an hour, one has plenty of time for a really good smoke.

From Imperial Airways Gazette, April, 1936: “Passenger fined for smoking after steward told him it was forbidden: Rupert Bellville of Whitesclub, St. James’s Street, W., was fined ten pounds and three guineas costs at Croydon Police Court on 17 March for smoking in the Imperial Airways liner Heracles, contrary to the regulations. Bellville pleaded guilty. He was represented by Mr. St. John Hutchinson, K.C. Mr. Vincent Evans appeared for the Director of Public Prosecutions. Mr. St. John Hutchinson said that this was the first case of its kind in the country. He asked the magistrates to deal with Bellville as leniently as possible. He said that Bellville was an experienced air-pilot. There was no danger to the passengers, and he asked the magistrates to treat the matter as if it were a mere technical offence. He said that Bellville wished to apologise to Imperial Airways for the trouble and expense he had put them to.

From Muse Air Monthly, September, 1983: “You can’t describe it. You just gotta fly it. Plus, a clean, smoke-free environment aboard quiet super 80 jets. More than 70% of all Americans are non-smokers today. As anyone who has flown on commercial aircraft in the last 25 years can confirm, we knew all about how unpleasant a smoke-filled airplane can be. Muse Air changed that, and launched a new era in air travel in the process.”

Young:

Do you want to hear something really pathetic? When a passenger would have to be given oxygen, highly explosive oxygen, they only made us make the people in front, to the side, and to the back quit smoking! We’re talking about an airplane that could explode, and that’s all they required us to do. They don’t want to inconvenience those smokers.

From, How to be a Flight Stewardess: A Handbook and Training Manual for Airline Hostesses by Johni Smith (1966): “No smoking is permitted (1) between the gate and the parked aircraft, (2) on board the aircraft while it is on the ground, (3) during takeoff, (4) during landing, (5) in the lavatories, or (6) whenever the no-smoking sign is on…”

Young:

No, that’s not true. Absolutely. You could smoke in the lavatories. That’s why Varig Airlines went down in flames in 1973, and after that happened, they banned smoking in the lavatories. But we allowed smoking on every single square foot of that airplane until Air Canada went down in 1983.

“…Most airlines permit stewardesses to smoke in flight only in the flight deck area, where they are expected to remain for not more than a few minutes at a time. Some carriers don’t permit hostesses to smoke at all while in uniform.”

Lane:

A lot of flight attendants smoked. They’d sit on their jump seats and smoke.

Young:

And in the kitchen.

Lane:

And in the galley.

Young:

They all went to international routes because it was banned on domestic in 1990. All the people I knew that were smokers went to international.

Blissard:

It got to the point where I had so many people in the early days of no smoking when people weren’t taking the ban seriously.

Lane:

Including flight attendants.

Young:

Flight attendants and pilots were going into the john and smoking. I flew with them all the time. The crews weren’t even enforcing the ban. Smoking was finally banned in the johns in 1974. I’ve had five fires on my flights from smokers. Two of them were in the john. The others were in the seats.

Lane:

Also snubbing out butts on the galley floors. Cigarette burns all over the place, including our skirts!

Young:

Look at these. These are cigarette burns on my hands from walking down the aisles.

Lane:

They wrecked a couple of my skirts. I’d go by or I’d be on the cart and their hands would be holding it out in the aisle. This is one of the reasons that the FAA requires fire retardant material for our uniforms.

“We Were Damaged…”

Lane:

When the SP (Special Performance 747) came out we had No Smoking sections. In first class there were 4 rows of seats. And then there was a galley area with 2 emergency exits and jump seats and then on one side were16 seats of Smoking section. They knew it was going to fly long hours, so they put in a crew rest. Cockpit got theirs right behind the cockpit. Ours was put in right behind the first class Smoking section, and it was a little room with a key to get in. We had bunks so we could lie down. But where was the intake for the ventilation in that room? It came straight out of the smoking section of first class. If you were in there for 5 minutes, you were getting the same concentration of smoke as the smoking section and there was nothing you could do about it.

Blissard:

In the late 1970’s or early 1980’s I was flying in the back of a 727 going out of San Diego on a 3-day trip. The person I was flying with in the back had prematurely white hair. She said, “Look at the color of my hair. I just washed it before the trip.” Then she added, “I’m not going to wash it on this trip. Let’s check the color on the second and third days.” So we took off, and of course right after climb-out the No Smoking sign went off as it always did, and everybody lit up. She was flying position number two, so her jump seat was by the aft door, right behind the smoke, and all of it came back there toward her. About the second or third day of this trip her hair was yellow-brown. I wasn’t surprised, but it was just so graphic because her hair was white to start with and you could just see it change dramatically, as if she had dyed it. After the end of the first day you could see a change, and by the third day it was striking.

And all of us would pack clean clothes in our suitcase at the beginning of a trip and stash it in the cabin under a seat. We’d get to the hotel room, and we’d open our suitcases up for the first time since we left home before starting the trip. Our clothes would reek of smoke. And we were in a hotel room now where there was no smoke. You could definitely smell it. Our clothes, our hair, and everything else reeked, but so did those clean clothes inside our sealed suitcases.

Sudderth:

I did the same thing that Bland did, and I think a lot of flight attendants did. As soon as I would come back from my trip, I would strip in the garage and just leave my uniform in the garage.

Bland:

And either that afternoon or in the morning that uniform went to the dry cleaners.

Blissard:

But that gets back to when smoking was banned on the airlines. It was night and day. The difference was colossal. We were damaged and then we started realizing the damage we had was permanent. But the immediate relief was amazing. I mean, I went from having green stuff in my sinuses every single day of my life and never being able to clear a sinus infection, and having been on antibiotics constantly.

Lane:

I used to be a runner. I started complaining to my internist, “You know, I’m having a hard time getting my breath when I’m running. It’s like somebody put a vise around me or something.” He didn’t pick up on it. He’d say, “It’s temporary.” Or, “Does it cause you any problems in the rest of your life?” And so it was never studied further until I went to my pulmonologist. Boy, he picked up on it immediately. At that time it didn’t even have a name. He said, “I know what you have. I know how to treat it. But it doesn’t have a name yet.” He had to give it a name because of the insurance companies. He had to have a name to put with what I had. It was basically chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

What We Did About It

Lane:

When I started in 1954, Pan American did not allow pipe or cigar smoking. I hadn’t been a purser too long, and I had big fights with passengers. I think it was when we first got the DC7s and we were going from Honolulu to Tokyo. We hadn’t been in the air very long, and this passenger lit up a stogie. Well, I was busy in the galley and a passenger sitting behind him came back and said, “That man’s smoking a cigar! He’s making my wife sick!” This was a great, big 6 foot tall man, so I said, “Let me handle it.” I went up to him and said, “Excuse me, sir.” I was my nicest, conciliatory, smiley-faced person, and I explained that it was against Pan American regulations. I asked him to please extinguish his cigar. And that’s all you used to have to say to a passenger. So I went back to the galley, and two minutes later the other man’s back. “He’s still smoking that cigar! I’m gonna punch him in the face!” That’s all I needed was a fight in the cabin. I said, “Please, I’ll take care of it.” I again went up to this man, and his wife was sitting next to him. I felt so sorry for the wife, because she was crunched down in her chair. I said, “I’m sorry, sir, I asked you nicely to please extinguish your cigar. Now I must insist.” And he wouldn’t even look at me. I was telling this man with my hand signals, “Stay out of the way,” and in another two minutes I deliberately went past him and he was still smoking. It was the only time I’ve ever done it, in all the years I flew, but I went to get the captain. I told him what I was having a problem with and so forth. This captain was lily-livered; he had no backbone. He just walked back, turned around, and walked back up front. Didn’t stop and say anything to this passenger. I was furious. So the man kept smoking. Finally, I said, “Gee, I hope you enjoy Wake Island.” “Wake Island?” he asked, “Where’s that?” I said, “Well, we’re going to have to land there. I’m going to have to remove you from the airplane.” “Oh, that’s alright,” he said, “I’ll get another flight out of there in a few hours.” And I said, “No, you won’t. The only airline that serves Wake Island is Pan American, and once you’ve been removed from a flight they will never accept you for passage again. However, every six weeks they have a supply boat.” And you know, that cigar went out. I thought once we got past Wake Island he’d light up again, but he didn’t.

Young:

I was working first class on a Dallas to Washington D.C. flight one time (this was when we had Smoking and No Smoking sections on a narrow body airplane), and two of the flight attendants in coach came up to me and said, “Patty, you’ve got to come back here. There’s somebody smoking in the No Smoking section and everybody’s complaining.” And I said, “You’re big girls, you know what the regulations are. Go tell him to put his damn cigarette out.” “No, no, no, you do it really well,” they said. I shook my head as if to say, “I don’t understand this.” So I walked back and the guy was sitting in row 14 D, E and F across all three seats with his back against the window and one of the tray tables down, with his scotch and water, just smoking away. I stood in the seats in front of him looking down at him and I said, “Excuse me, you’ve been told three times to put your cigarette out, so put it out.” He just took a deep drag and blew smoke at me. I said, “You’re not going to believe this, but…” and I took the cigarette out of his mouth and stuck it in his scotch and water, and I said, “You light it again, and I’ll stick it in your ear!” Everybody started clapping. I mean this lady had a baby over her shoulder behind him and she’s clapping! And he said to me, with some European accent, “I cannot believe that you did that to me!” And I replied, “I told you you wouldn’t believe it. Do it again and we’ll have a re-run.”

Lane:

Another big, big problem was the lavatories.

Blissard:

We had people we knew were smoking in the lavs. They’d come out and they’d go to their seats. They’d reek so you knew what it was. You just told them, “If you do that anymore, we might have to land the flight.”

Young:

I would use my key to open the lavatory door, and I had my fire extinguisher in my hand. I would just stand there with the fire extinguisher, saying, “Is there a fire?” And they would be mortified.

Lane:

You would go in there, and they’d have put a sanitary napkin over the intake of the alarm.

Young:

There was the awful tragedy of that fire in 1973 on the Varig Airlines jet with a full load of passengers on a descent into Orly Airport in Paris. On the 707 they had three johns in the back. Somebody was in there smoking. When the flight attendant got back there, a fire had started. They didn’t know which one of the three johns it was in. By the time they got to the right one, the fire exploded in their face. When they opened the door it blew out and fireballed to the cockpit. My friend David photographed the cockpit crew hanging out of the windows. They depressurized the cabin trying to see to land. Nine people were in the cockpit trying to get away from the fire. A smoker had set the back john on fire, and when they landed everyone had died, because smokers have their rights. And then there was that fire that killed 23 people in Cincinnati, with eyewitnesses seeing that woman going into the john with her cigarette in her hand. So I wasn’t real nice with people going into the john smoking.

Sudderth:

Patty’s right about the crew members smoking. I had not flown international until ’96. I had gone through a divorce so I needed the extra money. Patty got wind that I’d gone international. She called me up, and she said, “Are you crazy? They still smoke on international.” I said, ”I know Patty, but I’ve got to make my house payment.” I would bid Caribbean trips, because they had that funky rule where two hours or less you couldn’t smoke, so I’d do the Miami-Guatemala, Guatemala back to Miami, and then lay over in the Caribbean. There was no smoking. But on some of the long haul South America flights, when I first started out, I could smell smoke. I’d go to the back and wouldn’t see anything. The cabin was dark, nobody was in the lavatory, so what’s the deal? It was the crew! It was my fellow flight attendants! They would go into the bathroom and take a few puffs, then they would immediately flush it so that the lingering air would go away. It didn’t dawn on me that it was my co-workers who were addicted. They got very sneaky and very tricky. One time I was working a Rio flight, the only non-smoker on the whole crew, and I went on my rest break to take a nap for an hour. I kept smelling smoke, so I went to the back and saw that this crew had built an apparatus. They made a kind of tent thing in the back of the 767 galley. They took the cart so it’s kind like in a cubby hole in the galley, and there’s a return air vent. What they would do is go inside where the carts usually are and they would smoke and blow it into the return vent. The only reason that they stopped is because when I saw the apparatus I said, “What the hell is this?” They were looking a little sheepish, and saying, “Well, you know, it’s so hard for us.” I have taught Recurrent Training (Emergency Procedures Training) since 1990. Once a year we had to go through the training, and I’m an instructor out at the Flight Academy. So I said, “Look guys, you’re the crew. You cannot do this. I’m going to have to report you.” When they realized that they were going to be in big trouble, the tent came down.

Young:

I was getting off the bus at the airport when one of the girls I used to fly with looked at me and said, in front of what must have been 50 people, “Goddamn you, Patty Young! Because of you I’ve got to fly international so I can smoke.”

Lane:

Some smokers would ask for a No Smoking seat because the air was a little better. Then every 30 minutes they’d walk back and have their cigarette under our noses.

Young:

Something could be done about it because anytime there was a high concentration of smoke they had to turn the No Smoking sign on.

Lane:

That brings in the issue of ventilation systems. They had air packs on the engines. Once they were off the ground they would try to get by with a single air pack, because it took fuel to run these air packs. They would try to get by with as few air packs as they could.

Blissard:

“Air packs,” meaning, what pressurized the air. It took fuel to pressurize more air. So in the 1970’s or 1980’s the companies started telling the crews to start removing air packs.

Lane:

By removing she meant just turn them off.

Blissard:

I don’t know about other airlines, but we did remove some because the companies started to realize that we were going up to the cockpit all the time and saying we needed more air. Some of the pilots were sympathetic with this, and they would leave the air packs on. The airline’s response was to remove them.

From the September, 1989 issue of Flight Log, newsletter of the Association of Flight Attendants: “The new generation of aircraft has made things only worse. To save fuel, these planes re-circulate more old air than do older planes—up to 50% of it—substantially reducing the intake of fresh air. One of these aircraft, on which I have flown many times, is the airbus A310. There, we often suffer from headaches, nausea, difficulty catching our breath, and dizziness caused by passive smoking. Sometimes we must breathe from portable oxygen bottles in order to feel a little bit better. In addition, the airbus has a button in the cockpit called the “Econ Flow Valve” button which carriers have instructed pilots to use to conserve fuel. When activated, the button restricts the intake of fresh air by an additional 33%, while conserving fuel at a rate of only 0.8%.”

Sudderth:

It makes me wonder about their airplanes, because their flight attendants were getting very, very sick. They dragged their feet horribly on enforcement. They only did it because they had to. Even when the law went into effect the airlines didn’t make sure you enforced the law.

Lane:

They put it in your manual, and that’s the law. You’re supposed to enforce what’s in the manual.

Young:

But with American they would have been quite happy if we had sort of ignored it a little bit. We were the last ones to go non-smoking to Hawaii.

Blissard:

You see, we had Bob Crandall as president of American during those years when smoking was being banned, and he was a chain smoker.

Young:

They were starting to have marketing meetings at the time…all these premium flight attendants, the pursers, the ones flying the positions on the wide bodies, had to go to these marketing meetings. They had them all over the country and sometimes 500 people would show up. The issue about smoking on the airplane was making a lot of news. I was getting phone calls from San Diego, from Los Angeles, from Chicago, from Dallas. People would call and say, “They were talking about you today at the marketing meeting.” And they would say, “Mr. Crandall, what about this Patty Young story and getting smoking off the airplane?” He’d be standing at the podium and he’d go, “Oh, the Patty Young story!” He’d push himself to the side and he’d laugh and he’d pull his jacket, pull his cigarettes out, hit the pack, pop one up, take his cigarette out, get his lighter, light it, and then stand to the side and blow smoke, and he’d say to all of them, “Does that answer your question…about taking smoking off the airplane?”

Sudderth:

Crandall made no bones about the fact that he could have cared less about the quality of air in the cabins.

Lane:

We were disposable commodities.

Sudderth:

He could have cared less about flight attendants having a safe working environment.

Young:

And he was smoking on non-smoking flights. I’ll tell you one story to give you an idea. I was on a trip to Seattle, and I was in first class. We were on a full load, with only three flight attendants. This was on a DC9 stretch 80, which means the ventilation system started in the back and came to the front. Somebody was smoking in back, but I thought they were in front because the whole first class kitchen was full of smoke. I looked at all the passengers, I looked in the lavatory in first class, yet nobody was smoking. Everyone said, “Boy, I sure can smell the smoke.” Sure enough there was a passenger smoking in the rear john. The smoke came through the john door and all the way to the front of the airplane. So I took his ticket and identification and gave it to the captain. He looked at me and said, “I’m not gonna fuck with it.” And I said, “Well, I’ll tell you what, I will.” So when we landed I said to the agent I needed to have somebody to meet the flight because I need to deal with this fellow. He’d broken mandated federal law by smoking in the john. The captain came flying off the plane and grabbed the agent by the arm. All these passengers were furious that he had been smoking in the john. And then several passengers came back from the terminal onto the airplane just to tell me, “Your captain is up there apologizing to all the passengers for any inconvenience they were caused…by you.” The agent didn’t know what to do. He was just beside himself. The captain left me at the airport, took the rest of the crew, didn’t say a word to me, and went to the hotel. One of the flight attendants stayed behind. She was so angry, she started crying. I got to the hotel on my own and the next day at 5 o’clock in the morning, I went downstairs where the captain was sitting by the fireplace smoking. A flight attendant came up to me and said, “Hi, I’m the number one (lead attendant) on the flight going to Dallas.” And I said, “Well, there must be some mistake, I’m the number one on that flight.” But then I realized what was going on and I said, “I bet there’s not a mistake.” I looked over at him, and I said, “Hey Miles. Why are there two number one flight attendants on this flight?” He replied, “Because you’ve been kicked off the flight.” So I had to fly back as a passenger, and I was helping this flight attendant because she was brand-new and didn’t know what she was doing. He saw me helping her and he accused me of trying to poison him. When we landed, management met me, kept me in a room for about 5 ½ hours, and told me never to hassle a passenger again for smoking. They took away my ID, my cockpit keys, my travel privileges, my manual. So I made a phone call to someone, John Galipault…

Blissard:

I put together a survey with Dr. Charles Tate, a chest physician in Miami, of what effects flight attendants thought they were having, and it was printed in our Association of Professional Flight Attendants union newsletter around 1982. The union said that this one got a bigger response than any survey they ever ran.

From the September, 1989 Flight Log, newsletter of the Association of Flight Attendants:

“AFA members lead fight to stop smoking on aircraft

What if you couldn’t read your child a goodnight story because your voice was damaged from the cigarette smoke you breathe at work? What if you were told you had only five to seven years to live unless you stopped working in a career you loved? AFA members Cathy Gilbert-Silva and Connie Chalk have faced these dilemmas. At a June hearing before the house aviation sub-committee Cathy Gilbert-Silva, a non-smoking flight attendant, testified that last year she needed to have surgery on her vocal cords to strip them of the polyps and nodes they had developed. ‘My health problems have changed my life. Sometimes I cannot read to my son. I can no longer sing in my church choir.’ Gilbert-Silva is a lifetime non-smoker. A lung specialist diagnosed her with chronic lung inflammation and told her she would die within five to seven years unless she stopped working in smoky cabin air.

They have over 20 years seniority. They bid non-smoking flights whenever possible. It [the ban on smoking] made all the difference to me. I felt better. I did not wheeze as much. I never felt like I was strangling. I felt healthier. Less than two years ago bidding for any non-smoking trips would not have been a possibility for Chalk or Gilbert-Silva, but thanks to AFA members’ efforts, in April 1988 a congressionally mandated temporary smoking ban went into effect.

Blissard:

A flight attendant in San Diego had to quit because of allergies she got from the smoke, and she received a $10,000 out of court settlement

Lane:

Years ago when I was with Pan Am, around 1973, there was a young doctor in the Public Health Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital who started doing his own survey. I was in a union meeting, and we were asked who would volunteer to be his guinea pigs? I said I would because at that time I was having a lot of problems with coughing. We kept a periodic log of what we thought the air was like on the flight. One time I had just come in from a long trip from Hong Kong, on the SP, the Special Performance 747. I flew those a lot. I went into the doctor’s office to give him some blood or whatever they were doing to me, and I was coughing so hard he had to give me a shot of something to calm me down. And he said, “You have to see a pulmonologist.” I just called it my “SP cough,” because I was coughing all the time. There was never any time that I wasn’t. Because of my pulmonary problems, I filed a worker’s compensation case against United Airlines, and I won.

Young:

I will tell you that AFA (Association of Flight Attendants), the United Airlines union, got involved in the non-smoking issue far before our union did. Originally, AFA said they weren’t going to get involved. I stood in their offices in Washington D.C.! I was furious. And I said, “If you think that you are above a class action law suit, then I will sue your ass. If I have to picket from Seattle to Miami to get flight attendants to sue your ass and my airline’s ass, we’ll do it.” Not long after that, AFA said that they were going to work in some way to try to get smoking off the airline.

Sudderth:

They should have been at the forefront. You would have thought that all the airline unions would have been saying, “What can we do to protect our flight attendants?” They’re working in this environment. It’s not healthy. You’d have thought they were wondering what they could do to help the membership. When I first started flying, I was hesitant to say anything. I just couldn’t believe it. This was my office. I was working in a flying ash tray. And a flight attendant said, “You need to get in touch with Patty Young, because this is something that she’s fighting against.” There was no phone number exchanged, but we have hanging files in our operations area. That’s our mail drop. I left a note that said, ”Hello, flight attendant Jane Smith gave me your name and I’m interested in trying to get smoking off the airplanes, and someone said I needed to talk to you.” I wrote my name and my phone number, and she called me.

Young:

When we started flying, it was like being a movie star. One out of every 1200 who applied was accepted. But here’s what the airline really thought of me. What I did was write Crandall, the CEO, a letter telling him that I wanted him to quit smoking because we cared about him so much! I’ve still got a copy at home. Telling him how much we cared about him and that we wanted him to quit smoking so he’d be around to lead the airline. And he wrote me back a letter and said, “I really hope I run into you some time so we can go to lunch.” So then I wrote him another letter and said, “Would you please help us get smoking off the airplane?” It was a total set-up. I sent him my first letter which was only to bait him, and I will be happy to admit to that. It was a total bait to try and get on his good side. Not that I thought he had any good side at all. And then…

Sudderth:

…he wrote, ”I cannot make a public statement against smoking.”

“Can you imagine the reaction of community leaders and the many thousands of people who work for the cigarette companies to an anti-smoking initiative by American Airlines?” “As you pursue your efforts I hope you will consider their impact on others. There are a great many people whose lives and welfare would be adversely impacted by further anti-smoking legislation. In advancing your cause, I think you should carefully consider the other guy’s point of view. …because we would damage our stockholders, our business and ultimately our employees. We shall not oppose the spread of no smoking legislation since I can understand the desire of many to avoid smoking’s passive effects, but we cannot advocate it.”

Blissard:

I think that the membership, especially toward the latter years, was really suffering. And leadership was doing nothing. Yes. At one point the union could have thought that we can’t get enough flight attendants to actually step out and say anything in support of this because they’re afraid to lose their job. They’d all say, “We have payments, we have bills…”

Young:

I was called in numerous times and told I was going to have to quit my fight to get smoking off the airplane. And I just looked at them and said, “I’m going to have to be dead to quit this fight.”

Sudderth:

Your supervisor would call you in and say…

Young:

“…This is no one else’s problem but yours. No one else is complaining about this but you. You’re going to have to stop.”

Sudderth:

I went into my supervisor and I said, “I love my job, and I love what I’m doing but I can’t breathe. I get off the airplane and I’m sick.” It was really downplayed. I said, “I can’t believe it. I’m so excited to be here, but my work environment is so hazardous. Isn’t there anything I can do?” And she said, “I don’t think it will ever change.”

Smoking Ban Takes Effect

“I can’t tell you how much I admire those flight attendants who actively fought for the ban on smoking on airlines. I feel very much a part of this, because it was I who convinced Air Canada to let us do the clinical studies on cotinine on their airline. Without that we never could have gotten the support of the House of Representatives and the Senate in getting the non-smoking bill passed. In traveling I have talked to many flight attendants about how much better it is these days. If someone says to me, ‘What’s the most important thing you accomplished while you were in Washington?’ I always say, ‘Well, with the help of some others, it was getting smoking off airlines.’” –C. Everett Koop. M.D., special communication to Tobacco Control

Young:

As soon as Congress passed the rule banning smoking on flights of two hours or less, American Airlines went in and made flights longer.

Lane:

That was expensive because people were paying crews based on these flight times.

Blissard:

Like Bland says, we’re paid only by air time or block to block, door to door. So, if you add 15 minutes to all these flights every single crew member is paid at whatever rate they are paid at which for the pilots is really high. So this cost a whole lot of money for them to do this.

Young:

Well, it went 2 hours or less for just 2 years, right? And then it went.

From the Smoker’s Flight Guide, February 20, 1989: “The Smoker’s Flight Guide contains quick reference airline schedules for the major U.S., Canadian, Mexican and Caribbean traffic producing origin and destination cities. …Smoking should be permitted on all flights appearing in this publication. Nonstop flights appear in boldface type. One-stop and connecting flights contained herein permit smoking on each segment.”

Sudderth:

What we would do in Miami, because no one in the flight crews that I flew with smoked, if we had a flight that was kind of borderline, like 2 hours and 4 minutes (technically a smoking flight), we’d get together and agree that we didn’t want to have to put up with the smoke. So when we’d make the announcement, the number one (lead attendant), would say, “Welcome aboard our flight from Miami to Guatemala. Our flight today is 1 hour, 59 minutes.” It was clearly on the paper at 2:03. I didn’t want to have to put up with the smoke, so it was 1:59. And people would say, “I thought this was a smoking…,” and you’d say, “Sorry!”

Young:

Even when the Smoking sign would go on you’d say, “It’s a mistake.”

Sudderth:

It depended on how supportive of a captain you had. Sometimes if you had a really cool captain, then no problem. You know what my biggest pet peeve was when smoking was still permitted? A smoking flight attendant would say, “Just sit on my jump seat and smoke.” When that smoking sign would come on all of a sudden there would be 3 or 4 people from the non-smoking rows plop their butt in row 30 and light up! And then they’d go back up and sit in non-smoking. I’d see them coming and I’d say, “What are you doing?” And they’d say, “Oh, I need to smoke.” I’d ask, “Well, can I see your boarding pass? That’s a non-smoking seat. You’re not coming back here and smoking up my area.” Patty always told me, “Stick to your guns, Lisa.”

Blissard:

Smokers themselves often couldn’t stand sitting in the smoking section.

Lane:

I wouldn’t even let a flight attendant sit on a jump seat next to me and smoke. I was a purser and I could say, “I’m sorry, you’ve got to go somewhere else.”

Blissard:

The group ANR, Americans for Non-smokers Rights, was one of the best in helping us. They followed up. They were great, and they never let up until smoking was off of the planes. Also, I have to say that Patty was the most effective and the most dedicated person, and the one who also could get out in the public.

Young:

The only people in Congress who helped us get smoking off the airlines were Democrats. The Republicans sabotaged everything. In Congress, the only people who ever gave me a sincere ear were the Democrats—like James Oberstar, Frank Lautenberg, Dick Durbin, Ted Kennedy, and Martin Frost.

Blissard:

There were a lot of us in the background that were doing other things we were more comfortable with like research. I did a lot of background stuff. I think almost all of us were passing petitions. And we were going to supervisors trying to find some inroads somewhere. But, you had to be really careful. You had to do it on the sly. And, also, counting burn holes on airplanes. I was always passing sheets around to people in my base and saying, “Count the burn holes.” Then we’d talk to John Galipault of the Aviation Safety Institute. We tried turning it in to the FAA. We tried approaching it from the stand point of safety.

Young:

In 1983 I documented the burn holes just on escape slide hatches. Those escape slides were not even usable. Thirty-five burn holes on one escape slide hatch because they sit on the jump seat, put the cigarette on the escape slide hatch, and the cigarette falls back into the escape slide. Thirty-five burn holes!

Blissard:

Another approach was to sue the tobacco companies. Norma Broin was a flight attendant from San Diego who got lung cancer and she wanted to sue. She grew up a Mormon in Utah and never was around smoke at all, or smoked or drank. It was the tobacco company lawyers’ worst nightmare. It was perfect.

Lane:

They could depose her all day long and couldn’t find anything.

Blissard:

But we couldn’t find lawyers to take the case. Every lawyer said, “You know, nobody’s ever won against Big Tobacco. And we’re not going to pour money down a rat hole.” Finally, Stanley and Susan Rosenblatt in Miami took the case. “Yeah…it’s nuts,” they said, “but it’s the right thing to do.” They not only accepted the case, but they took it through all kinds of legal loopholes to certify it as a class action. At last, the case was settled out of court.

Young:

Over the years, a lot of flight attendants said, “Oh, let’s get smoking off the airplane,” and that’s the last thing they ever did about it. People said it before I ever said it. But that’s all they did was say it. They never did a damn thing about it. I will go to my deathbed saying, and I mean this: I think the entire non-smoking movement went worldwide because of the flight attendants. Our stories were told over and over every single day, on every single flight. We told it thousands and thousands of times. And we let that passenger take our story home. The history of this fight didn’t start with us. It started back in about 1926 when people began smoking on airplanes. The terror and tragedy of this started when they allowed smoking on the airplane.

Canaries in the Mine Symposium

2003 and 2005, FAMRI Annual Scientific Symposium

November 30 through December 2, 2004, San Francisco Airport Museums, San Francisco, CA

Up in Smoke Exhibition

2003 World Conference on Tobacco or Health, Helsinki, Finland

September 15, 2004 through March 15, 2005, San Francisco Airport Museums, San Francisco, CA

Reproduced in print, Tobacco Control, March 2005, Vol. 13, Supplement 1

2007, Buffalo Niagara International Airport, Buffalo, NY

Blum A. Up in Smoke: The Airline Flight Attendants Fight to End Smoking Aloft. Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society. https://csts.ua.edu/exhibitions/2004-famri/. Published March 20, 2017.

Dr. Alan Blum, MD

Professor and Gerald Leon Wallace, MD, Endowed Chair in Family Medicine

College of Community Health Sciences

Tuscaloosa, AL 35487

(205) 348-2169